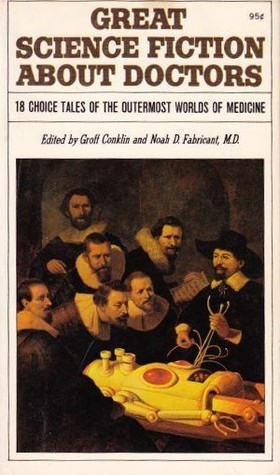

Book Review: Great Science Fiction About Doctors edited by Groff Conklin and Noah D. Fabricant, M.D.

While medical doctors are common and important in science fiction, stories directly about them or the field of medicine are a bit rarer. It was one magazine’s speculation that it would be difficult to fill an anthology with really good stories on the topic that convinced the editors that they could actually do just that. The eighteen stories in this anthology are arranged by last name of author, with several of those writers being themselves M.D.s.

Each story comes with an introduction by the editors, some more interesting than others as they talk about the authors and the themes of the story.

“The Man Without an Appetite” by Miles J. Breuer, M.D. starts out the volume with a rarity, as it was originally published in a Czech-language magazine and this was its first known publication in English. A doctor is contacted by the wife of a scientist he knows. The scientist no longer eats anything she cooks, and won’t tell her why. Does he hate her cooking? Does he hate her? Is he dying? He has assured her it’s none of those things, but is evasive about giving any other explanation. Can the doctor check on him?

The doctor checks up on his old friend. The scientist looks healthy, but doesn’t eat anything at restaurants or dinners. He’s evasive about why he isn’t eating in public, but does mention that he’s been running some fascinating experiments in his laboratory and the doctor should totally stop by some time for a demonstration.

Busy with his own stuff, the doctor puts this off, but soon the two men find themselves on a scientific expedition to an isolated island. The scientist gets stranded alone on the island without food supplies for a few weeks due to plot shenanigans. When the doctor and the others return, the scientist looks just fine, and finally gets around to explaining what’s going on.

I was struck by the sexism/poor treatment of the wife involved in this story. The explanation is in fact simple to understand, even if the science behind it would be complicated. Presumably the scientist had a snazzy presentation planned for any intellectual equal who came by the laboratory, which is why he didn’t explain it to the doctor before. But even if the wife couldn’t follow the details of the technology involved, she could easily have grasped the outcome and wouldn’t have to have gone through months of emotional turmoil.

“Expedition Mercy” by J.A. Winters closes out the anthology. The first expedition to Minotaur perished, so a second expedition staffed primarily by expert physicians has been sent to investigate. It’s a medical procedural, as the team follows protocols and evidence to arrive at a diagnostic result. It’s very good at the technical side (though missed some technology that’s been invented since) but some of the banter is a bit much. I did like the tension-breaking final bit, where the lead doctor explains that a particular situation could never happen…and it immediately does.

In between, there’s some gems. “Rappacini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” by Edgar Allan Poe are excellent nineteenth century tales that should need no introduction, but are well worth rereading.

“The Little Black Bag” by C.M. Kornbluth is about a future doctor’s bag transported back through time and winding up in the hands of a delicensed alcoholic. For him, it represents a possibility for redemption, but for his receptionist, it represents big money and it ends in tragedy. The future is the same one presented in “The Marching Morons”, in which stupid people have severely outbred the intelligent ones–you may have seen Idiocracy, which uses a similar premise.

“Mate in Two Moves” by Winston K. Marks, about a plague of insta-love, is remarkable in being the one story in the volume that has an intelligent and capable woman as a positive portrayal and the actual hero of the story. Indeed, once the twist is revealed, we can only marvel at her iron will and professionalism. (Homosexuality is never mentioned–evidently the disease also makes you attracted to the opposite sex automatically?)

Other stories are more interesting for their innovation. “The Psychophonic Nurse” by David H. Keller, M.D. has a woman who is struggling with post-partum issues, and her husband who decides to take an engineering approach to the problem. He creates what we would now call a robot in the form of “a black Mammy” controlled by spoken numbers from a gramophone to be the baby’s nursemaid. It has good features, but there are some bumps in the road. I liked the attention paid to how this innovation would be affecting the public.

But the story is also clear that the mother is in the wrong. No matter how skilled a writer she is, and we’re given to understand that she’s crackerjack, a mother’s only career should be raising her children.

“Compound B” by David Harold Fink, M.D. has a doctor create a serum that temporarily makes people highly intelligent. It only works on people who have a high melanin count. Since the doctor turns out to be highly racist, he doesn’t want to give black people an advantage over his white compatriots. He names the serum “Compound A” and spends the rest of the story looking for a serum that will work on pale people, the titular “Compound B.”

His wife is more clever than the doctor (though neither of them is wise) and comes up with various ways to keep the research funded, including becoming missionaries despite not having religious beliefs. She eventually secretly sells the secret of Compound A, which in a roundabout way leads to World War Three.

And then there’s “Family Resemblance” by Alan E. Nourse, M.D. which I reviewed previously. It’s not exactly science fiction, everything in it could happen with the technology of 1953, but it very much fits in this anthology, and has an amusing twist.

I’d say my least favorite story was “Out of the Cradle, Endlessly Orbiting” by Arthur C. Clarke, which is about the first permanent settlement on the Moon, and shoves the medical relevance into the final paragraph.

Content note: period sexism and racism, anthropophagy, murder, ableism, lookism, some gruesome medical stuff. Bright late teens readers should be able to handle it.

Overall: A fine anthology for science fiction fans who are interested in medical matters and have a tolerance for some outdated attitudes. It’s been reprinted several times so should be easily findable in used bookstores.