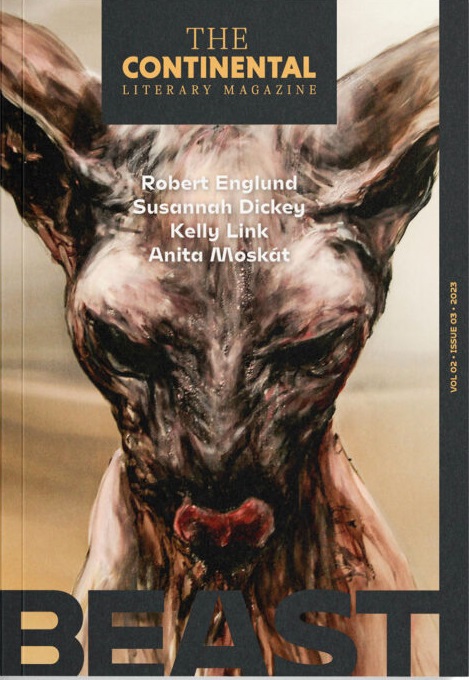

The Continental Literary Magazine: Beast (2023) edited by Sándor Jászberényi

The Continental is a Hungarian literary magazine dedicated to widening recognition of Central European authors in the English-speaking world. It comes out quarterly, and I happened to notice a copy at the bookstore. The theme of this issue is “Beast”, both actual animals and the beast inside human hearts. To start with, it’s got an excellent physical design, nice to look at and to hold. The page count is boosted by having a two-page introduction to each author, and a limited number of words per page, but it looks classy. I especially like that the names of authors and translators have pronunciation guides next to them.

“The Beast Within” by Sándor Jászberényi is the editorial introduction, briefly going over the etymology of “beast” and how its meaning has shifted, and talking about some of the content.

“Those Who Walk Away” by Catherynne M. Valente (I’ve reviewed her book Deathless on this blog) is an essay about the gender roles assumed in how literature talks about “the beast” and the difficulties women have experienced over the centuries. Modern society has loosened the shackles a bit, but some are still uncomfortable with women expressing their own relationship to their inner beast.

[smiling face icon] by Anita Moskát follows on well from the essay, talking about young women who on the surface bend over backwards to please and to fit into their appointed feminine roles, but underneath are about to snap. Or maybe it’s just one woman; she keeps saying “we” but the circumstances are not exactly universal. Some disturbing imagery here.

“Lobsters” by Susannah Dickey is mostly about a couple having a conversation in McDonalds, during which the title creatures and how humans treat them come up disturbingly. As so often happens, the conversation is really about something else, and there’s a dark secret between them.

“María’s Bees” by Zsolt Láng takes us to Bolivia, where a nursing home worker learns the backstory of a beekeeper. There’s some symbolism going on, I think, but I’m not getting it.

“Asterion” by Maciej Płaza is a retelling of the minotaur myth from the point of view of the imprisoned creature. At first it seems to be trying to demythologize the story, Asterion being the product of a more mundane infidelity than congress between bull and human, but as the tale progresses it takes on more mythic tones, at least from Asterion’s point of view. Content note: child abuse.

Then there’s an interview with Robert Englund, an actor and director most famous for playing modern film monster Freddie Kreuger in the Nightmare on Elm Street series. He talks about his own childhood fears and nightmares, how he got into the role, the kind of monster Mr. Kreuger is, and the future of horror movies. No big reveals here, but interesting for a horror fan.

This is followed by a section of paintings by Ágnes Verebics, who does a line in disturbing art of animals, distorted or covered faces and pieces of women. Creepy, and would make good illustrations for horror novels of the less gory kind.

“The Female’s Tale” by Noémi Szécsi is science fiction, set in a lecture hall a couple of generations after human animals and non-human animals have learned how to talk to each other. A surviving scientist from the old times introduces the moment of her big breakthrough. Content note: animal abuse.

“The School of the Animals–A Tirade” by Franzobel takes place in an Austrian zoo at closing time and into the night. A new zookeeper patrols the grounds, thinking he is alone. He’s not, but then he’s truly alone…or is he? Scary, for a bit.

“Executioners and Victims” by Noémi Saly is a historical essay on the job of executioners in Budapest, and a particularly notable event connected with one of them. Always fun to learn some history I hadn’t even thought about before!

“The Lieutenant and the Tin Soldier” by Gábor Zoltán is set after the end of World War Two. A lieutenant of the Arrow Cross (Hungary’s own fascist party, which I talked about a bit in my review of Siege 13) is about to be executed for war crimes, and talks to a tin soldier he took from the apartment of an executed child. We learn about his motives, which turn out to be…petty. Human, but his tragedy is of his own making. Content note: Anti-Semitism.

“Creature” by Kelly Link has a new mother alerted to the death of an old (if distant) friend. The friend’s niece notes that despite the distance, the protagonist was the deceased’ closest friend and offers the chance to go through the apartment for anything she wants. The deceased was a cat enthusiast, and there’s something in the apartment that strongly resembles a cat. The creature follows the protagonist home and displays some un-cat-like qualities. The ending is ambiguous.

“What’s That Drawing on Mum’s Shoulder?” by Ivana Dobrakovová features a girl who has regular visits with a psychologist which she thinks are a waste of time. Her mother initially comes across as the more noxious sort of vegan, but it’s rapidly apparent that there is something actually wrong with her, and it’s gotten worse since the pandemic. Content note: self-harm.

“Ukranomicon” by Gábor Nyári rounds out the fiction pieces. It begins with a Polish man chained to a child zombie during World War Two. But abruptly, we learn that this is a scenario in a Call of Cthulhu game being played by two (drafted) Russian soldiers in Ukraine. They’re passing time while hiding in a bombed-out building after being separated from their unit. They’re a little miffed by the Ukrainian soldiers calling them “orcs”, given they didn’t want to invade. However, the genre of the story might be going from “the horrors of war” to just plain horror…

There’s poetry scattered throughout the issue, but it’s all the modern poetry I don’t “get.” Might be brilliant in the original Hungarian.

Of the fiction, I liked “Asterion” and “Ukranomicon” the most.

For American readers, I suspect fans of Catherynne M. Valente and Robert Englund will be the ones most anxious to get copies. But it’s got a good mix of stories and articles, and physically looks excellent, so recommended to anyone interested in Central European literature.