Movie Review: Samurai Rebellion (1967) directed by Masaki Kobayashi (Japanese title: Joiuchi–Hairyo Tsuma Shimatsu, “Rebellion–Receive the Wife”)

The time: 1723-1727 C.E. during the Shogunate period. The place: The Aizu province ruled by Lord Matsudaira, a bit north of Edo. The person: Ichi (Yoko Tsukasa), daughter of a minor vassal. Ichi has been arranged to marry another vassal’s son, but this is overridden by Lord Matsudaira (Tatsuo Matsumura). As Matsudaira has only one son, he needs a spare heir in case of unfortunate circumstances so that his clan does not lose their fief. He’s set his eye on the pretty and healthy Ichi to be his mistress and bear his children. It’s framed as a request, but you don’t disobey the lord’s wishes. Not and stay healthy anyway. When her betrothed is pushed into breaking off the engagement, Ichi has little choice to comply, despite finding Lord Matsudaira sexually repugnant.

Ichi bears a son. When she returns from her postpartum recovery, Ichi discovers that the lord has picked up an additional mistress, one who is happy for the opportunity. In other words, Lord Matsudaira could have had a consensual relationship all along, rather than forcing himself on Ichi. The young woman understandably loses her temper and gives Matsudaira what for.

Offended but not allowed to just kill her, Lord Matsudaira dismisses her from the castle and “requests” that Ichi be married off to Yogoro Sasahara (Go Kato), older son of escort group leader Isaburo Sasahara (Toshiro Mifune), The Sasahara family isn’t too keen on this. Isaburo has personal reasons for this, remembering that he was “requested” to marry into the Sasahara clan because their head wanted his superior sword skills to enhance their prestige, and as a low-ranking samurai he was in no place to refuse. His marriage with the nagging Suga (Michiko Otsuka) has been loveless, with just enough physical contact to create Yogoro and his brother Bunzo (Tatsuyoshi Ehara). Only Isaburo’s stoic acceptance of what can’t be helped has sustained the formal relationship for the last twenty years.

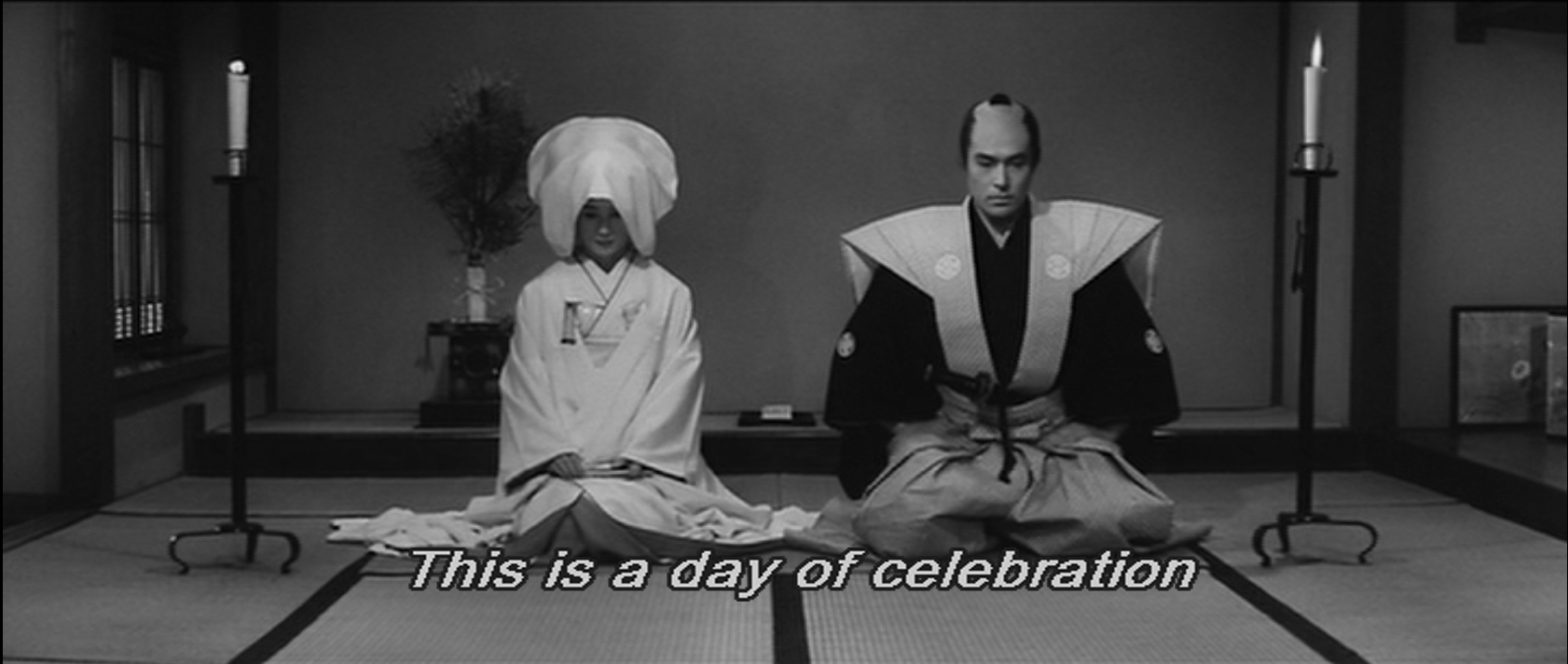

Isaburo tries to dodge the burden, angering Chamberlain Yanase (Masao Mishima) until Yogoro agrees to the match, based on his father’s example of obedience. Yogoro and Ichi are married. Much to everyone’s surprise, the actually quite nice Ichi and kind Yogoro hit it off, and the relationship becomes a deeply loving one. They have a daughter, Tomi, and Isaburo takes the opportunity to retire, as Yogoro has now shown himself a responsible adult.

A few months after Tomi’s birth, word comes from Edo that Lord Matsudaira’s older son has died. Ichi’s son Kikuchiyou is now the heir, and it won’t do for the heir’s mother to be married to a lower vassal. (The other concubine apparently hasn’t gotten pregnant yet.) Steward Takahashi (Shigeru Koyama) comes to “request” that Yogoro return his wife to the castle and her mistress status. This goes down as well as you’d expect, and leads to tragedy.

The director was already well-known for his prior films Harakiri and Kwaidan, but this was his first time working with legendary actor Toshiro Mifune, who also co-produced the movie. Apparently it took a lot of work in post-production to make all of Mifune’s lines audible. He uses architectural details well to give many of the shots a claustrophobic, rigid feel. A particularly striking symbolic moment is Isaburo talking to Ichi in a raked sand garden about their possible responses to the situation. He moves off the paved path, and his footprints spoil the symmetry of the lines.

Also an obvious theme is Isaburo’s fighting style, as described by his best friend, border guard captain Tatewaki Asano (Tatsuya Nakadai). When pressed, fall back, if pursued, fall back again, until the moment comes to switch to offense, then wait for the moment where the opponent makes a mistake to end the bout. He’s been pursuing this policy in his personal life as well, so it’s a bit of a surprise to his wife and his superiors when he stands his ground at this final outrage.

This story takes place during a peaceful time in history, and there’s surprisingly little violence for a samurai film for most of the run time. At the beginning, a sword is only used to slice a straw dummy, and it is mentioned that Isaburo and Tatewaki have been deliberately avoiding a sparring match. There’s a brief moment of fisticuffs when Lady Ichi loses her temper, but the serious violence is all in the last half hour as no way can be found out of the social traps. And then it’s a bloodbath.

Another thing that struck me was the cowardice of most of the superiors. The lord doesn’t make his requests directly, but sends underlings. And those underlings will try to pass the responsibility down the ladder rather than face the unpleasant reactions they know they’re going to get. Tatewaki manages to rules-lawyer his way out of one such assignment because he agrees with Isaburo, but eventually is forced into a position where he cannot avoid fighting his friend.

The soundtrack is also good, relying on instruments appropriate to the time period, and diegetic whenever appropriate.

Content note: Sword and gun violence, usually fatal but not particularly gory. Suicide. Domestic violence. Implied marital rape. Peril to a child. Breastfeeding. Due to the nature of the social conflicts and the length of the movie, I’d say older teens on up.

A well-made samurai tragedy with an unusually strong focus on the central female character’s emotions and concerns. Strongly recommended to those can handle that it is, yes, a tragedy.