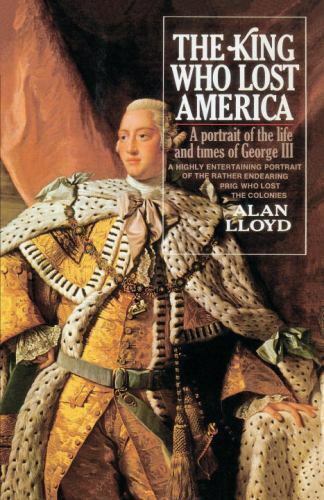

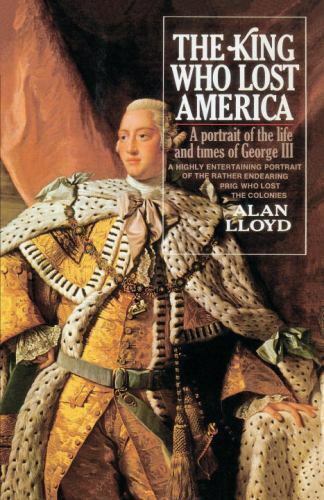

Book Review: The King Who Lost America by Alan Lloyd

I’ve reviewed more than one biography of George Washington, hero of the American Revolution and first president of the United States of America. But there was another George involved in the Revolution, King George III of Great Britain. This biography is about him.

It begins with a brief biography of the first two Georges, his great-grandfather and grandfather, who were princes of Hanover invited to take the throne as the other major claimant was Catholic and thus ineligible. They weren’t good at speaking English nor terribly interested in managing Britain, so Parliament got in the habit of running affairs itself most of the time. Not getting on with their heirs ran in the family, so George III’s father Prince Frederick was sent off to live with his family in relative austerity.

Sheltered from the intrigues of court, young George grew up strongly religious, a firm believer in temperance when it came to alcohol, and disinclined to extra-marital sex. His parents also instilled in him the belief that kings should be sovereign, and that he would need to take back the reins of power. George’s father predeceased his grandfather, and it was thus that he inherited the throne at a relatively young age.

George III’s stubbornness and tendency towards autocracy caused him no end of trouble with his various ministers and Parliament, and eventually the American colonies. He never seems to have caught on to why the masses weren’t grateful for his benevolent tyranny.

As you might expect from the title, the heaviest focus is on the years leading up to and during the American Revolution. George’s stubbornness (and general support from most of the English population) in refusing to negotiate with the American colonists as equals rather than as rebellious children who needed a good smacking did a lot to push the Americans towards independence. He (and the pro-war people in general) vastly misread the military situation, and feared a “domino theory” loss of territories and prestige if the Americans were allowed to leave.

There’s a chapter on the “Gordon Riots” of 1780. Harsh anti-Catholic laws had been enacted after the Church of England won its position as state church, and this was causing problems, especially in the heavily Catholic areas of Ireland. (As one would expect, anti-Catholic laws only deepened their religious convictions.) So a Catholic Relief bill was passed to slightly improve conditions, allowing Catholics to own land and get military promotions, among other reliefs. This did not go over well with the militant Protestants, including Lord George Gordon, who incited riots on the subject.

George III was okay with the Catholic Relief bill, but not with the later Catholic Emancipation bill that would allow Catholics to hold offices in government. He was, after all, the Defender of the Church of England as he’d sworn to be at coronation. He was however favorable to Wilberforce’s efforts to abolish slavery on religious grounds.

Later in his reign, George III started having mental breakdowns. This led to him being unable to control the government as tightly as he had before, and eventually he was forced to allow his son George IV to be regent as George III was no longer able to fulfill his duties as king.

This is a popular history rather than a scholarly one, so it skimps on a lot of the in-between details and the analysis is more surface than deep. There’s no internal illustrations in the paperback edition, but there is a bibliography and index for those who want to do further study. I found the writing comprehensible and interesting. I did spot one spellchecker typo.

King George III might not have been a sexy king, but he had interesting foibles, and was probably the most competent of the first four Georges.

Recommended reading for British royalty fans, and for American Revolution buffs who wonder “what the heck was King George thinking?”