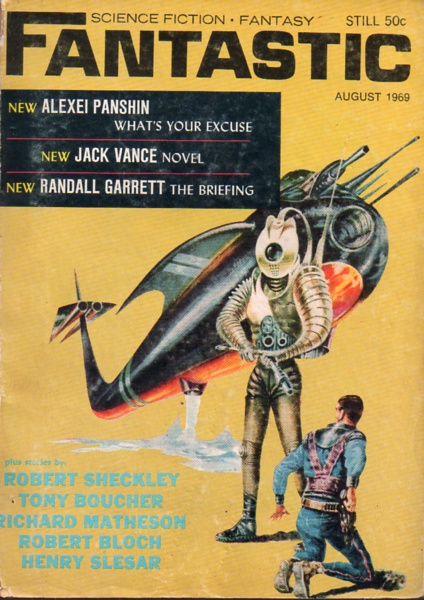

Magazine Review: Fantastic August 1969 edited by Sol Cohen

The opening editorial is by Ted White, the new managing editor. He talks about the decline in “fiction magazines” (the Saturday Evening Post had recently ceased publication for the first time) and is sad, but points out that times are always changing. He also mentions his failed magazine project “Stellar” but hopes to bring some of the stories purchased for that to Fantastic in the new editorial direction of “stories that are good, but don’t quite fit in other magazines.” He also plugs the 27th World Science Fiction convention in Saint Louis.

“What’s Your Excuse” by Alexi Panshin is one of the stories originally slated for Stellar. A psychology professor is playing a cruel prank on one of his co-workers, calling it an “experiment”. But he may not understand who is the real butt of the joke. As Mr. White explained in the editorial, this is not a story that is “science fiction” but wouldn’t fit in a non-genre publication because the narrative attitude is SFnal. It’s an okay short.

“The Briefing” by Randall Garrett is a short-short shocker in which spacefarers consider interfering in the culture of a primitive world to prepare them for the galactic war to come. Since the whole point of the story is the final twist, I won’t spoil further.

“Emphyrio” by Jack Vance is the second half of a novel. Ghyl Tarvoke, a woodcarver and son of a woodcarver, lives on the planet Halma, in the welfare-state of Ambroy. As a child, he learned the fragmentary story of Emphyrio, a culture-hero who spoke truth to alien oppressors and was executed for his pains. (And yet somehow is treated as the victor.) Ghyl’s father had a bit of obsession with Emphyrio, and wanted to bring a bit more freedom and democracy to the nobility-ruled Ambroy.

This did not work out so great. Ghyl’s father was “reconditioned” and became a shell of a man, dying not too long afterward. Ghyl drifted for a while, then fell into the company of “non-cup” men that pursue various irregulatory activities for profit. By happenstance, Ghyl learns that a small starship will be leaving the planet that a band of clever hijackers could take over. Part one of the plan goes well.

But the Lords aboard affirm that they won’t pay ransom for hostages even at the cost of their lives, and Ghyl learns that his fellow criminals do not share his moral qualms. He and the remaining Lords are marooned on the first inhabited planet available and are forced to make their way to civilization. It’s Ghyl’s first prolonged interaction with Lords and he becomes aware that their behavior is peculiar even accounting for the class differences.

Separating from the others, Ghyl makes his way to the city, and discovers a reproduction of one of his father’s works on sale. Since Ambroy has made mechanical reproduction of art illegal, he’s shocked. Ghyl’s even more shocked to learn that the original is in the intergalactic Museum of Glory. The monopoly that controls the sale of Ambroy handicrafts to offworld has been systematically cheating the artisans with lowball payments for centuries!

Ghyl makes a deal with a local merchant to bypass the monopoly and buy art directly from Ambroy. But when they arrive, the guilds are too hidebound to understand they’d profit by this plan and afraid of rocking the boat. The disguised Ghyl is recognized, and arrested. His interrogation is the framing device for the story to this point.

The Lords present are visibly shaken by his “confession” but are ordered by their leader to ignore any implications they might be tempted to draw. Ghyl is sentenced to “expulsion” into the neighboring country. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the method of expulsion is a very slow death trap. One that’s in poor condition due to being used so seldom over the centuries, allowing Ghyl to find a way to escape and make his way back to the merchant’s starship.

Ghyl develops a ruse that allows him to divert an art shipment to the merchant’s hold. They head to Earth, and sell the art, making enough profit, even after setting aside a generous payment for the artisans of Ambroy, that Ghyl is independently wealthy. Earth, as it happens, is the galaxy’s repository of historical knowledge, and Ghyl finally learns the full story of Emphyrio. He then makes a trip to the planet where it happened, and finally puts together the pieces of what’s really going on in Ambroy.

“You shall know the truth, and the truth will make you free.” But that freedom may come at a cost.

This is a slow burn novel, full of Jack Vance’s trademark alien culture details. Ghyl has a strong ethical sense, trying to remain true to his core values even when forced to do things he finds immoral. He adheres to the “least harm” ethic until near the end of the story and even then it’s more like tearing off the bandage to not prolong the pain.

Less good is the treatment of women as accessories to the male characters. They have agency within the story, but mostly as to which man they choose to be with, and don’t move the plot at all.

The remaining stories are reprints from other Ziff-Davis magazines of the 1950s.

“Let’s Do It for Love” by Robert Bloch has public relations man Mortimer approached by chemist Joe Stevens, who has developed a formula that makes people love. No, not an aphrodisiac “love potion” but genuine love for everyone and everything. Properly applied the effects are permanent. Imagine a world without hate, fear or prejudice! Problem is that Mr. Stevens’ previous concoctions have produced results like spotless leopards and hairy billiard balls and he’s something of a laughingstock in the scientific community.

But Mr. Stevens does have a cash retainer that Mr. Mortimer desperately needs for his own purposes. Even an encounter with Joe’s long-suffering wife Dorothy, who gave him the money to buy a better used car, doesn’t entirely dissuade Mr. Mortimer, especially after he sees the formula used to make a cat and canary fond of each other.

Unfortunately, the pair soon discover that the press, the legal system and politicians all have reasons to not want love to win, and the three are about to team up to crush the formula. Mortimer manages to prevent this with some adulterated Mountain Dew ™ but a domestic dispute between the Stevenses brings a new crisis. There’s a reasonably happy ending, but the love formula will not be coming to market.

I don’t like the “science-hating wife” cliche but it’s well-justified here.

“To Fit the Crime” by Richard Matheson tells the story of Iverson Lord, an aged poet who is something of a genius in his use of language, and treats his less intellectual family and in general everyone else like dirt. He’s dying now, and takes the opportunity to express how much he’s been put upon and how much he hates his next of kin. Then he goes to his own special Hell. Again, the point of the story is the twist ending, so no spoilers.

“The Star Dummy” by Anthony Boucher is about Paul Peters, a ventriloquist who thinks that his evil dummy is talking to him. He might be a little crazy. But this comes in handy when he goes to the zoo and there’s a weird creature trying to communicate with the wombats. Turns out this is Tarvish, an alien. He didn’t recognize humans as intelligent because they don’t give off psychic vibrations. Paul does, for unknown reasons (but he can guess.)

Tarvish is looking for his mate, who crashed on Earth a bit ago. Paul comes up with the idea of teaming up with Tarvish for a ventriloquist act to see if publicity will allow them to contact Vishta. It very much works, and Paul also meets a mate.

This is a very Catholic story, and the aliens have their own version of the Pater Noster.

“Fantasy Books” is the book review column. Fritz Leiber takes a look at three “hard-core” SF/F books. He notes that detailed description of sex acts can quickly become clinical or cliched, so you also need a good rest of the book to appeal. The one he likes best of this trio is The Image of the Beast by Philip Jose Farmer, “close to being very good.” But also notable is Season of the Witch by Jean Marie Stine, about a male murderer forced into the body of his female victim. The author was then named Hank Stine. The book was turned into a movie, Memory Run, which I have seen. (There’s a lot less sex in the movie.)

Ted White reviews Isle of the Dead by Roger Zelazney, and admires the bottom-up construction of a mythology for the purposes of the plot. He compares it favorably to a Travis McGee story.

“The Hungry” by Robert Sheckley has a baby notice that a creature the adults cannot see is performing petty mischief to make them miserable, angry and hating. And the cat is doing nothing to help. Can the baby save the day?

“The Worth of a Man” by Henry Slesar has a disabled veteran in a postapocalyptic city convinced he is being followed. His therapist pooh-poohs the notion as paranoia is endemic among the survivors of the late war. But just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you. The title turns out to be rather literal.

The issue closes with a fan essay, “Tolkien and Temperaments” by Bill Meyers. In it he talks about how he came to love the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and the influences in his life that made that author’s output strike home for him. Mr. Meyers grew up in the Deep South, and uses the word “darkies”, but it’s an interesting look at one fan’s life.

I liked “Star Dummy” and “For Love” best, but what I read of “Emphyrio” was good, and it’s overall a strong lineup of authors. Keep an eye out for this one at garage sales and used book stores.