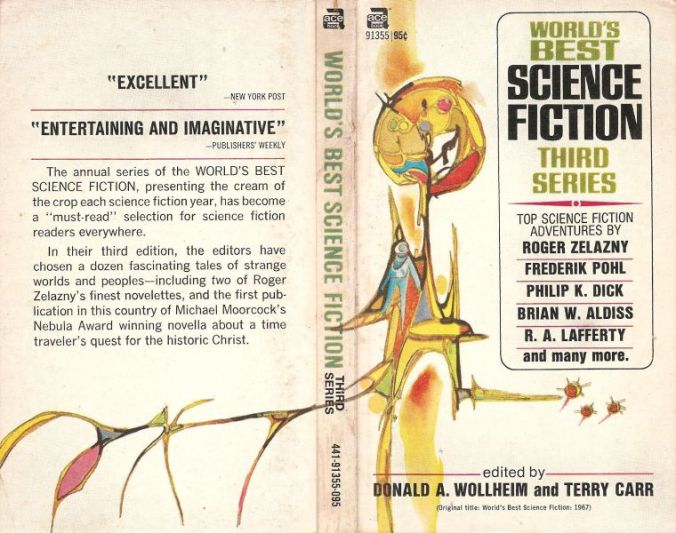

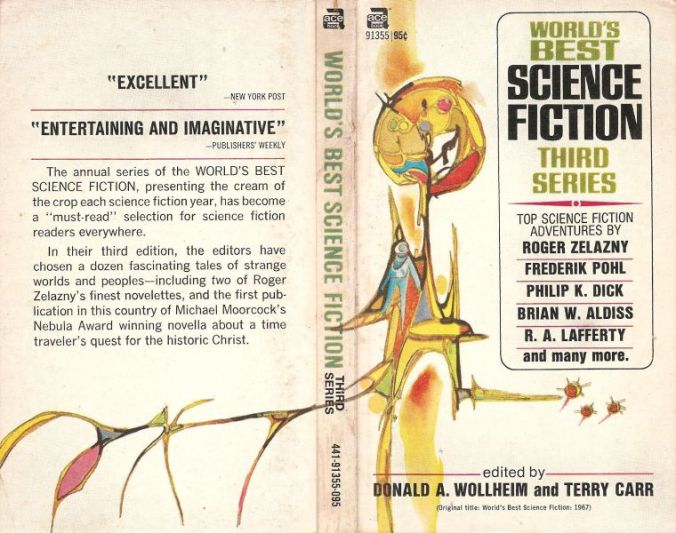

Book Review: World’s Best Science Fiction: Third Series edited by Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr (also printed as “World’s Best Science Fiction 1967”)

The introduction to this volume of science fiction stories from 1966 mentions that there was a tendency to longer stories in the field, perhaps because many of the ideas required more fleshing out. And while the quality is as always somewhat uneven, 1966 seems to have been a good year for science fiction.

“We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” by Phillip K. Dick is of course the story on which the movie Total Recall was based. See my earlier review of that. Ordinary office worker Douglas Quail dreams of Mars, but knows he will never be able to go. Especially with his wife’s constant reminders. But a company named Rekal promises that they can implant false memories of having taken a trip to Mars, complete with a subplot where he’s a secret agent, and souvenirs of his supposed voyage.

Except that to the horror of the Rekal workers, when they try to implant the new memories, it turns out Quail has real memories of being a secret agent on Mars, memories that Interplan had erased. Now that he kind of remembers them, Quail has become a danger that cannot be ignored.

There’s a final twist that the movie skipped in favor of more action.

“Light of Other Days” by Bob Shaw has a young married couple go shopping for “slow glass” in a picturesque part of Scotland. Slow glass lets light through very slowly, so what it shows now happened some years ago. Imagine having a view of nature even in your dismal city apartment that’s good for a decade!

The future isn’t all rosy. Women can still get fired for getting pregnant, which has happened to the young wife, and the husband’s poetry income isn’t going to get them into a house. Plus, they’ve come to the realization that neither of them is keen on having a child. But slow glass will give them something pretty to look at while being miserable.

The local man that sells slow glass out of his cottage seems nice enough, if a touch eccentric. But there’s something wrong with the family seen through his picture window. “Light passes both ways.”

“The Keys to December” by Roger Zelazny starts by having Jarry Dark born as the result of genetic engineering to work for a mining company on a non-Earthlike planet. But he and several thousand other prospective employees are stuck on Earth when that planet’s sun goes nova. Jarry’s smart, and he and the other world-orphans eventually make enough money to consider “terraforming” an uninhabited planet so that they can live there.

As Jarry periodically wakes from suspended animation to check on the progress of the climate transformation, he discovers something alarming. The changes to the planet’s ecosystem have triggered human-type intelligence in one of the native species. But even more drastic changes are to come, and the natives might not survive those. Jarry’s faced with an ethical dilemma.

“Nine Hundred Grandmothers” by R.A. Lafferty I’ve written about before. When a space entrepreneur discovers that the people of Proavitus do not die of old age, simply getting smaller and sleepier, he realizes this is a key to learning how the universe began. Or would be, if he could convince the oldest ones to tell him!

“Bircher” by A.A. Walde is a murder mystery set in a future where murder is almost unknown because the police are so good at catching the perpetrators. So when an impossible corpse shows up, it’s a threat to the police commissioner’s job. The title is a bit of a clue, as the case ties back into the long-defunct John Birch Society. This isn’t a fair play mystery, as several important bits of information are gathered offscreen and then revealed at the climax.

One thing about the story that seems too plausible is the government tracking everyone by their credit cards.

“Behold the Man” by Michael Moorcock was understandably somewhat controversial in its time. Karl Glogauer is a follower of Carl Jung who wants to have proof of the historical Jesus, as he wants to believe in Christianity. So when he gets a shot at using a time machine, Glogauer jumps at the chance. But as Glogauer arrives in ancient Palestine and attempts to locate Jesus, he learns that he may in fact have to become the Messiah himself.

The story uses the best available historical research of the time, but steps away from full commitment to “realism” by for example using the modernized/Westernized names of people. Some bits of fulfilled prophecy are coincidence, others directly invoked by Glogauer, and some turn out to have been made up later once Glogauer was dead.

Content note: anti-Semitism, bullying, torture, crucifixion.

“Bumberboom” by Avram Davidson is set in the far future, after the Great Gene Shift has separated humans into various humanoid species. (No one knows what the original humans looked like anymore, though some subgroups are quick to advocate for their own phenotype.) The wanderer Mallian realizes that the crew pushing around the title piece of artillery, also called a “Juggernaut”, have long lost any knowledge of how to make it work. He exploits that fact, but can he do any better with the lost technology?

Part of the Statue of Liberty shows up, but without a modern human to cry “You maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you!” (Planet of the Apes, 1968) it is just an object of speculation.

“Day Million” by Frederik Pohl was published in men’s magazine Rogue, so could get away with some prurient subject matter. The plot is paper-thin, “boy meets girl” but it takes place on Day Million, so the boy is a cyborg and the girl is genetically male, among other strangeness of the far future. Mr. Pohl points up the existence of intersex people even in 1966, and asks the reader if their own lives wouldn’t seem strange and impossible to their distant ancestors. It’s less of a story and more of an attempt to really put the “speculative” in speculative fiction.

“The Wings of a Bat” by Paul Ash is set in the distant past as the doctor of a time-traveling mining camp is asked to take care of a sick pterodactyl. The doctor is a grump who is not a veterinarian and particularly dislikes pterodactyls. But everyone else in the camp dotes on Fiona, so try he must. More or less heart-warming ending.

“The Man from When” by Dannie Platcha is a short shocker about the cost of time travel. Cute, but not particularly good.

“Amen and Out” by Brian W. Aldiss has people consulting “the gods” in shrines either at home or on their backs. The gods give advice and admonishment, but are often cryptic or unhelpful. Several people get advice on a single day, which results in one of the immortals the government keeps not exactly imprisoned leaving the compound where he’s kept. Turns out this immortal has more to do with the gods than was first apparent.

The story relies on the hippie drug culture of the 1960s either lasting, or being recreated some centuries hence.

“For a Breath I Tarry” by Roger Zelazny (again) also takes on religious themes. After Man has vanished from the world, the mighty computers Solcom and Divcom argue about which of them should be in charge. They agree to a contest. If Frost, the greatest servant of Solcom, can be tempted into serving Divcom, then Solcom will relinquish his claim to sovereignty.

But what can tempt Frost? As it happens, he (and the pronoun is deliberate) is interested in understanding the nature of Man. But in order to understand Man, do you not have to become him?

There’s a lot going on in this story, and it will reward discussion with other readers.

Overall, this is a strong collection with a high proportion of excellent stories. While the best of them have been anthologized elsewhere, having them together might be a reason to track this particular volume down.