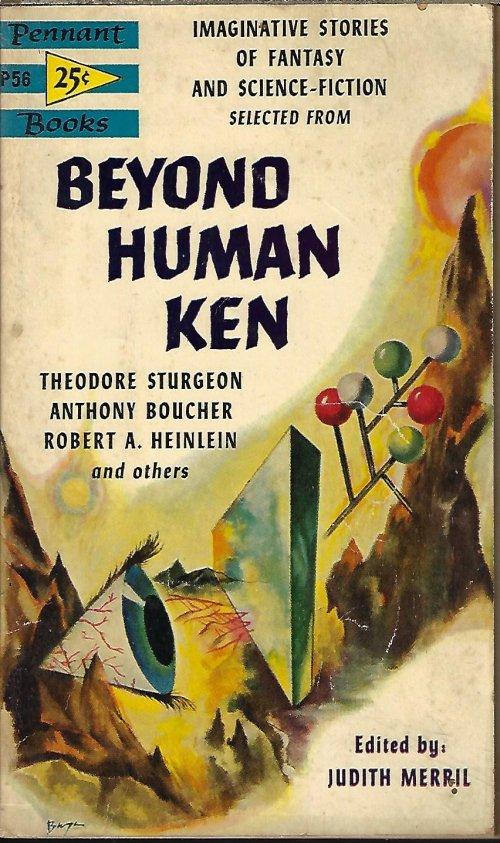

Book Review: Beyond Human Ken edited by Judith Merril

This 1954 paperback anthology is a partial reprint of the 1952 hardback of the same title, choosing twelve stories of the original twenty-one and skipping the prefaces that were in that edition. The theme is non-human beings of various kinds, pulled primarily from the science fiction genre. Each story is introduced by the editor, who gives a little information about the author and the kind of creature within.

“The House Dutiful” by William Tenn leads off with…a house. Physicist Paul Marquis is taking his bacteriologist colleague Esther Sakarian out to look at some prime Canadian backwoods acreage he’s purchased to build a home for his fiancée back in Boston. Esther’s a (1950s) second-wave feminist with a chip on her shoulder, but she’s smart and Paul trusts her judgement on anything that doesn’t involve gender. She’s not too impressed when his practical joke is revealed–there’s already a perfectly fine house on the property!

Except that there wasn’t one the last time Paul saw the place. And it looks exactly like the one he’d been planning–including details he’d never put down on paper! Esther confirms that yes, there’s no way this exact house could have been built this fast without anyone else at their research facility knowing, especially as that there’s an appliance in the kitchen they’d discussed but isn’t commercially available.

Paul stays the night while Esther goes to fetch Doc Kuntz, M.D. and thorough skeptic. He soon learns that the house really is receptive to his every wish, though it has some limitations. (It can’t print the pages of a book that Paul hasn’t actually read, for example.)

Next morning, Esther arrives with the doctor, some testing equipment, and a “Dear John” telegram from Paul’s fiancée. Seems she wasn’t nearly as thrilled by the prospect of living in Canada as he’d assumed. The house is determined to be ancient alien technology, from a mining camp that was abandoned eons ago. It’s thrilled to have a master again, and will do anything to make him happy.

And that’s when this turns into a horror story. Esther’s feminism? Gone, replaced by a desire to be a Fifties housewife for Paul. Paul thinking that maybe this might be a bad thing to do to Esther? Gone. The doctor’s worry that the house could take over the world to ensure that Paul is happy living in it? Vanished. Chilling.

“Pride” by Malcolm Jameson has Old Tom, one of the last few free robots, reaching the end of his repairable lifetime. He’s put off repairs, becoming more and more dysfunctional, as he knows that the repairs will only give him another decade or so and exhaust his savings, forcing him to sign himself over to a human master. And he has another plan in mind for those savings, a way to leave a legacy for the future.

As is common for stories about free-willed robots, some of the metaphor is openly about slavery and Jim Crow. (The name “Old Tom” is hardly an accident.) But another part is about learning what you can let go, and what you can do to make your life meaningful.

“The Glass Eye” by Eric Frank Russell has two extraterrestrial scouts land on Earth to pave the way for conquest. The gimmick here is that the aliens communicate by telepathy, something they learn from an abductee is not possessed by humans. Instead, humans rely on a crude visual sense. The aliens have run into this before, so Eenif the bold is equipped with a device that negates all optic nerves within a wide radius for his extended scouting while cautious Qvord stays in the ship and monitors.

What they haven’t encountered before, as Qvord belatedly realizes, is beings with sight with enough technology to create devices that see for them. And Eenif, in his overconfidence, has left a trail of blindness that can easily be extrapolated forward to the next town in his path…and backwards to the ship.

“Solar Plexus” by James Blish has two men abducted by a spaceship with a human brain. It seems a brilliant scientist had developed a method of hooking up a human brain and nervous system to become the controlling systems of a spaceship. Alas, the fools in government deemed his theories mad, and he was forced to rush the job using himself as the brain.

There are some major weaknesses with this prototype. For example, there had been no thought of installing internal cameras, so the ship cannot see what is going on inside it, having to guess what the humans are doing by what it feels when they interact with part of the ship. Also, the ship has lost all human empathy, seeking only to improve itself and turn others into creatures like itself. If the men don’t want to end up as spaceship brains, they’d better use the ones they have!

“Our Fair City” by Robert A. Heinlein is considered one of his rare “fantasy” stories in that the sentient whirlwind Kitten is never explained. It simply exists, and probably has done for decades before a parking lot attendant realized this and befriended it. When the boys at the local crusading newspaper learn about Kitten, they enlist it in a plan to expose the corrupt mayor and police department. It’s funny, but you can spot some of the smugness that really came out in Heinlein’s later work.

“The Compleat Werewolf” by Anthony Boucher is another comedic fantasy. Professor Wolf Wolfe of Berkeley’s German Languages Department is reeling from disappointment in love. He’s a young enough professor that him having an unrequited crush on a beautiful former student is more foolish than creepy. (Though we can tell from the fragments he tells us that she was the sort who flirts with professors to improve her grades.)

Out getting blotto, Wolf runs into Ozymandis the Great, an unemployed magician. His problem is that he only knows real magic, not showmanship. Oz reveals to Wolf that the professor is in fact a werewolf, needing only the proper magic words to change. Did I mention they’re both very drunk? Turning into a wolf sounds like a great idea!

Every werewolf story has its own rules. Since Wolf’s a voluntary werewolf instead of a cursed one, he doesn’t lose his human mind or develop an appetite for human flesh. On the other hand, he has a wolf’s vocal apparatus, which prevents him from speaking the magic word that will turn him back. He has to get someone else to do this, and Oz isn’t always around.

After an embarrassing incident that costs Wolf his job, he and Oz hatch a plan that will allow Wolf to use his powers to win over the lady he loves. Which goes immediately askew as Oz vanishes using the Indian Rope Trick once too often, and it turns out the local Satanist cult is a front for a Nazi spy ring. How’s Wolf going to get out of this one? Mostly happy ending, but content warning for suicide.

“The Wabbler” by Murray Leinster is about…well, the closest phrase we’d have is “smart bombs.” Or perhaps torpedoes. Dropped at sea, the Wabbler alternately drifts and swims ever closer to its target, sometimes lying still for long days. It calculates, but does not think. It’s a dry story, but a tense one.

“The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles” by Idris Seabright is a story I’ve reviewed on this blog before. It’s about exactly what it says, and could perhaps be taken as a metaphor for the dangers of capitalism. Or a straight-up warning about making deals with people whose rules you don’t know.

“What Have I Done?” by Mark Clifton was first published in these anthologies. An employment agent realizes that one of his customers isn’t human thanks to his long experience with reading people. It turns out that the man is an alien shapeshifter; “he” and his twenty-nine companions are the advance force in an effort to infiltrate human society and slowly replace it. Our protagonist can help them remain undetected, or they can go to Plan B, simply erasing the human race now.

The employment agent finally agrees, and helps the aliens become fully human–with one fatal flaw that will destroy them. Which then triggers the title question.

“Socrates” by John Christopher is a very British story. A professor at a radiation research facility stumbles across the caretaker Jennings beating puppies to death. Turns out that his dog had been inside the fence without protection, and given birth to a litter of mutants. The professor notes that the puppies have an unusually high alikeness for mutants, and that the one Jennings hadn’t killed yet has an unusually large braincase.

Since the professor’s current landlord won’t allow him to keep pets, he pays Jennings not only to spare the puppy, now named Socrates, but feed and care for him until the professor can take him in. Jennings, greedy as well as cruel, agrees. The caretaker promptly goes back on the deal as soon as he realizes that Socrates can be exploited, and runs off with the dog to become a trick act.

Jennings attributes his success as a trainer to liberal use of a whip, but it’s in fact Socrates’ intelligence to the point that he can talk, which the dog wisely conceals from Jennings but reveals to the professor. Unfortunately, Socrates still has some dog instincts, including loyalty to his cruel master. It ends in tragedy.

“Good-Bye, Ilha!” by Laurence Manning is another alien story. In this one, the alien is mistaken for an unintelligent animal by human scouts on its planet and adopted as a pet. It likes the humans, but quickly realizes that while humans are quick to make friends with creatures they like, they’re just as quick to kill ones they don’t. And the fact that there’s already a technologically advanced native species that would compete with the colonizing humans bodes ill for our protagonist’s people.

If its plan goes well, the humans will be convinced to try the next planet over…if not, the alien is willing to die still friends.

“The Perfect Host” by Theodore Sturgeon begins with a woman leaping out a hospital window to her death. The three witnesses see this, but cannot see her body on the ground. Strange things continue to happen. The story has several narrators, each of which supplies a piece of the puzzle. This takes a meta turn when one of the narrators is Theodore Sturgeon and the story goes very dark. Content note: suicide, domestic violence.

A good collection, though long out of print. The mostly 1940s sensibilities will grate with some modern readers, though the attempts at thinking in nonhuman skins helps some. “Our Fair City” is perhaps the most dated. “The Wabbler” could still have been written today.

Best luck searching through old bookstores!