Magazine Review: Astounding Science Fiction July 1939 edited by John W. Campbell

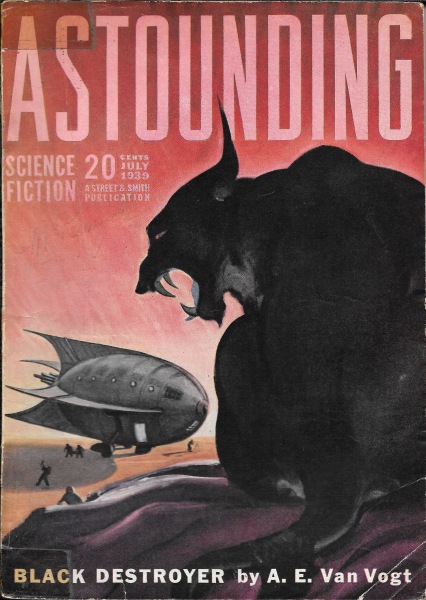

Astounding Science Fiction is now Analog, which is still being published; see earlier reviews on this blog. Today I’m looking at a key issue from the pulp days, July 1939. First, there’s this classic cover by Graves Gladney.

Up front is “Addenda”, an editorial by John W. Campbell, in which he updates the readers on the latest development in atomic science, the proof of existence of nuclear fission! It was a fast-moving field, so his previous editorial on atomic science had already been obsolete by the time it saw print.

“Black Destroyer” by A.E. van Vogt is the cover story, and the first published work by Mr. van Vogt. Coeurl is one of the coeurls, the dominant species of his unnamed planet. They were once an advanced scientific civilization, having developed atomic power and a means to make themselves functionally immortal. But this came at a price. Their bodies could no longer naturally metabolize id (phosphorus), requiring them to extract it from the snake-like id creatures that could not be domesticated.

This led to a food shortage, and the demise of coeurl civilization as they turned on each other for control of hunting territory. After thousands of years, Coeurl realizes to his horror that he has exhausted his territory’s supply of id creatures, having consumed them faster than they could reproduce. Just as he’s reconciling himself to a slow death by id starvation, a starship lands.

The Space Beagle is a scientific exploration ship named after the vessel that Charles Darwin sailed on, and the crew are mostly scientists and scholars. They’ve come to this remote planet as part of their mission, and are excited by the possibility of studying an alien life form that comes right up to them. It seems intelligent, but they can’t communicate as coeurls communicate via radio frequencies and have control over vibrations.

Coeurl has grasped almost instantly the implications of space travel–his species never developed it as they had no moon on this sole planet in their solar system, and the nearest other star is 900 light years away. If he can learn the secrets of the human technology, Coeurl can unite his fellow coeurls, however many are left, in a voyage to find new sources of id, such as humans.

As soon as crew members begin dying, the humans realize that Coeurl (who they call “Pussy” due to a resemblance to Earth felines) is the culprit, despite Coeurl being careful to give himself an alibi. They badly underestimate the alien at first, learning that he’s immune to their primary weapons, but they have a few tricks Coeurl doesn’t know about, such as an understanding of history.

This is a very good first story, showcasing van Vogt’s skill at writing exciting narratives. It’s been an influence on speculative fiction ever since, being an inspiration for bits of Dungeons and Dragons, Dirty Pair and Alien. It also features some of the author’s trademark dubious social science; I suspect many historians would dispute his notion of how civilizations go through their life cycle.

“Trends” by Isaac Asimov is his first story in Astounding, but his third professionally published one. Post World War Two, American culture has taken a conservative turn. So far, so accurate prediction. However, this conservative movement has taken the form of a fundamentalist Luddite religious fervor, backlashing against technology and scientific innovation. John Harman wants to build a rocket that will take him out of Earth’s atmosphere, and he’s facing considerable opposition.

A fanatical spy manages to sabotage Harman’s first launch attempt, killing or injuring many onlookers. This is used as an excuse to crack down on scientists and their research in the name of God. But Harman himself has survived, and is secretly building a new rocket.

By comparison, it’s a weaker story notable only for its placement. Asimov would improve greatly over the next few years.

“Numbers Without Meaning” by John W. Campbell (under the name Arthur McCann) is a short piece about a publication that prints nothing but random numbers for use in experiments that require random numbers. Nowadays, computer programs can generate random numbers so I suspect the publication has ceased.

“City of the Cosmic Rays” by Nat Schachner is part of a series. Sam Ward, American of the Twentieth Century, Kleon, Greek of Alexander the Great’s army, and Beltan, Olgarch of Hispan in the far future have been thrown together by fate. Most of humanity perished in various catastrophes over the centuries. Hispan in South America was one of the few remaining civilizations, but has now been overrun by the rocket troops of Harg, a fascist underground society.

Our heroic trio tried to get help from the Individualists of Asto, who have immense psychic powers, but this failed because of their lethargy, and the one Individualist who did have any initiative sided with Harg.

In this story, the heroes are speeding through the sky above what used to be India, when they are summarily jerked several miles up to a flying city. Dadelon is unshielded from cosmic rays, and as a result mutations are common so that no two inhabitants look alike. (Shades of Attilan and the Inhumans from Marvel Comics.) Diversity is their key cultural trait; not only do they not look alike, but no two people study the same field (though some overlap) and each has developed their own unique method of self-defense.

The trio, seen as weird because of their relative sameness, warn of the Harg menace but get no cooperation as it would be anathema to the people of Dadelon to present a united front on any topic. Naturally, when the Harg rocket men arrive, each Dadelonian defends him, her or itself individually with their special abilities. They each manage to take out some enemies, but fall before the superior numbers and teamwork of the Harg.

The protagonists barely escape, hoping that the next civilization they encounter will be the one that can help defeat the Harg. The “Past, Present and Future” series appears never to have been collected, so you’ll need to dig to find out what happens next.

“Lightship, Ho!” by Nelson S. Bond is set on Pluto, where two lonely lighthouse keepers send out a beacon for space travelers and prepare the distant planet for eventual colonization, as well as watch out for space pirates. They’re shocked when the proximity alarms go off, warning of an intruder several hours’ travel away, and seconds later there’s a knock at the door.

It turns out that renegade scientist and pirate Red Armitage has developed a method to accelerate his ships to near-light speed almost instantaneously (and perhaps more impressively, decelerate them) so that any warning message about them will arrive at pretty much the same time they do. Now that he’s temporarily taken out the threat of Pluto’s lightship, Red can advance on Earth.

If only there was some way to send a communication faster than light! The physics seems dubious to me, but I don’t have the math to disprove it.

“Tools for Brains” by Leo Vernon is a fact article (Campbell was big on having science fact as well as fiction in the magazine) about the history of calculating devices from the abacus to the proto-computers being developed by scientists before World War Two. Mr. Vernon is careful to point out that calculators do not “think”, they merely calculate. Fascinating stuff!

“The Moth” by Ross Rocklynne is meant to be somewhat humorous. A spaceship construction company is offered a new engine that will allow faster than light travel, but the person offering it may be a plant from a rival company known for playing dirty. The FTL drive in question uses a principle that has some unsettling implications, which are used against the crooked owner of the rival company. The humor falls a bit flat for me.

“Brass Tacks”, the letters from readers column, includes a missive from Isaac Asimov, complaining that he was not being supported by other fans in his one-man crusade against “slop”, the inclusion of romance and other elements seen as appealing to female readers, in science fiction stories. (As you can imagine, his attitudes towards women often did not go over well even with other male fans.)

Damon Knight uses statistics to try to support his contentions about which artists should illustrate stories. And there are science discussions about kinetic energy, centrifugal force and how many crew members a spaceship would realistically need.

“When the Half Gods Go–” by Amelia R. Long is set on Venus, where a Martian exploiter gets a clever idea about posing as a god to take over a Venusian tribe and monopolize their trade goods. Unfortunately for him, one of the Earthling trade delegation is an atheist. The Earthling doesn’t convert the Venusians, mind you, but he does happen to remind them of their tests to see if a god is real. There’s some tense bits, and some acknowledgement that people may be trapped in unfavorable situations by social coventions.

“Geography for Time Travelers” by Willie Ley is about paleogeography, the study of what the Earth looked like millions of years ago. Probably out of date now, but a good survey of the field as it then stood.

“Greater than Gods” by C.L. Moore is the kind of story Isaac Asimov would have hated at the time. Dr. William Cory, leading biologist, is deciding which of two women he has feelings for that he should ask to marry him. As he’s contemplating their photocubes, torn between possibilities, Dr. Cory is contacted by his descendants from the distant futures. Both of them.

In one future, his research into a revolutionary sex selection process stalls out because his frivolous wife distracts him into other avenues. Female babies start outnumbering male ones by a large amount for unknown reasons, and Earth becomes a matriarchy. The future is peaceful but turns more towards contemplation and art than scientific progress, and the human race is slowly dying out.

In the other future, his ambitious wife makes sure the sex selection process is successfully launched, but before the long-term testing is complete. It turns out that children created using the process have a strong tendency to obey authority. America’s leader at the time has a vision of spreading American values to the entire world, and urges the production of more boys than girls to fill his army. The future humans have conquered the rest of the Earth, Mars and Venus, and are preparing to invade Jupiter. Science, particularly weapons technology, has advanced by leaps and bounds, but most of humanity is basically soldier ants following the orders of a small freeborn elite.

Neither future is appealing, even as Dr. Cory feels love for both of his future children. How can he decide? How dare he decide?

It’s an interesting look at how gender role assumptions might affect civilization in the long run if the imbalance gets too large.

Kurt Busiek did a story with a very similar premise for his Astro City series, and you might want to compare and contrast.

Overall, a solid issue with interesting content; getting hold of the original might be tricky, but most of these stories have been reprinted elsewhere.