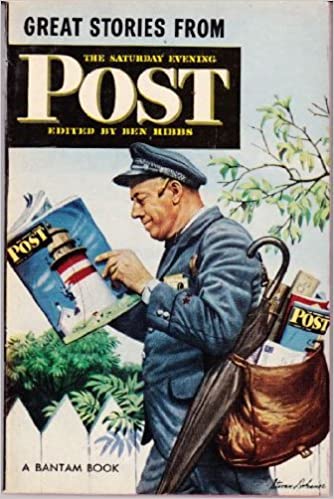

Book Review: Great Stories from the Saturday Evening Post edited by Ben Hibbs

For many years, the Saturday Evening Post was one of America’s most popular magazines. Every week, it would show fascinating photographs, interesting non-fiction articles and a selection of short stories and serialized fiction. With more than 200 short stories being printed in its pages every year, it’s not surprising that you could pull a “best of’ collection together. This 1947 paperback only pulls from the years 1942-1946 but still managed to find thirteen tales the editor really liked.

“Memo on Kathy O’Rourke” by Jack Sher is pretty obviously inspired by Shirley Temple, though much of it applied to Hollywood’s treatment of child stars in general. The publicity man assigned to the title character’s latest movie comes to realize (because he’s the only one she will talk to honestly) that Kathy is unhappy with her life. She likes performing, but her “stage mother” aunt is resentful of the child and insists on total control of her time. And the director, known for his abusiveness towards adult actors, is nice to Kathy in a creepy way and she doesn’t like the way he touches her.

A scheme is cooked up to allow Kathy to disappear for a few days so she can interact with ordinary children and play in a normal way. But what about the long run?

“The Bishop’s Beggar” by Stephen Vincent Benet concerns an ambitious young bishop whose carriage accidentally runs over a man’s legs. Crippled for life, the man rejects offers of employment that don’t require legs, choosing instead to become a beggar on the steps of the cathedral. The bishop’s ambitions become derailed, but perhaps he gains something more precious. A very Catholic story.

“The Murderer” by Joel Townsley Rogers is a tense tale of a farmer who is looking at his dead wife in a field and contemplating how he’s going to explain this when a deputy sheriff pulls up. Will the farmer’s recounting of events reveal the truth?

“The Flood” by Conrad Richter takes place in Texas in the early days of the Civil War. A rancher enters into a marriage of convenience with an orphan girl so there will be someone to look after the place while he joins the Confederate army. They have barely been introduced, let alone like each other. On the way out to the ranch, they get caught in a flood, and learn considerable more about each other’s character.

(The man is depicted as having the motive of “Yankees can’t tell me what to do” rather than anything having to do with slavery.)

“Tugboat Annie Wins Her Medal” by Norman Reilly Raine takes place immediately after World War Two. Annie did good work in the Merchant Marine during the late conflict, but still feels down that because she’s a woman, she wasn’t allowed to do any of the fighting. But it turns out there’s one Japanese submarine crew that hasn’t realized the war is over, and Annie devises a way for her tugboat to trap the enemy.

Tugboat Annie was a long-running character in Post stories, and popular enough that the stories kept being bought. Unfortunately, it looks like there was only one collection that’s long out of print (and does not include this story), so tracking down the individual stories will take some work. Content note: period racism towards the Japanese.

“Grown-Up Wife” by Muriel Bruce has a white trader in Navajo territory dismayed when his daughter arrives home to announce she’s divorcing her recently returned husband. Seems he’s been getting pretty high-handed since he got back from the war. Also bad is that his top jewelry maker, Smiling Woman, plans to retire now that her own husband is back, as working with silver is a man’s job.

It’s an interesting look at gender roles between different cultures, and when it is time to modify old ways versus keeping good traditions. The ending leans toward the Magical Native American cliche as Smiling Woman performs a Navajo ritual that somehow fixes everything.

“Mr. Whitcomb’s Genie” by Walter Brooks is straight up fantasy. A New England farming couple discover a lamp that contains a spirit that will grant their every wish. They’re very sensible folk, so things do not go nearly as badly as they easily could have, but in the end they’re just as happy without a genie.

“The Return” by Noel Langley takes us to South Africa and Rhodesia. Pomfret and Kennedy form a partnership in a tobacco farm and a strong friendship. But their relationship becomes strained when Kennedy brings home his new wife Margaret. She’s a failed golddigger who’s settled for Kennedy because he’s got at least a modest income.

World War One comes and Pomfret and Kennedy both volunteer for the army. Kennedy is blinded, and Pomfret must decide whether or not to reveal that Margaret’s written a “dear John” letter (she’s not aware of the blindness, she’s just run off with another man.) It’s a tale with a bitter ending. Content note: outdated terms for native Africans.

“Rebound” by Robert Carson is a more lighthearted take on a soldier’s return. Jimmy had a quickie wedding before being shipped out, and barely knows his wife. He faces temptation as he waits to be mustered out. Will he pick the pretty nurse who’s set her cap for him, the wife who may or may not be waiting in New York, or a lovely stranger he’s just met?

“Some Kinds of Bad Luck” by C.S. Forester starts with fireman Jimmy contemplating an exceptionally good poker hand before he’s called out to a fire at a chemical factory. He saves the day, but loses the game. Then it turns out this is a science fiction story (written in 1943, but the latter part set in 1951) as after World War Two wraps up, Jimmy is the man in charge of the Supervisory Committee of International Relations’ new air force. This United Nations-like organization is meant to keep peace in the post-war world (the war ran until about 1949 in this alternate universe.)

Jimmy learns of a political coup about to take place somewhere in Europe, and must act quickly to put out this fire before it spreads. There’s some interesting discussion between Jimmy and the coup leader. The leader wants justice for his oppressed people, and if he doesn’t act now, the majority government will clamp down and forbid reform; Jimmy points out that the leader’s justice will result in injustice towards the majority as their country again becomes embroiled in war.

Jimmy’s plan successfully stops the coup without immediate loss of life, but he still can’t win at money gambling.

“The Question” by Dana Burnet is about theodicy. A preacher is faced with the question of why soldiers have to die in war, even in a cause their parents know is righteous in the eyes of God. In his answer, the preacher allows a conversation between obvious stand ins for the parents and the Almighty. As anyone who’s studied theodicy knows, it’s a thorny and complicated question (unless you shortcut to “there is no God”), so the answer may not satisfy the reader.

“You’ve Got to Learn” by Robert Murphy tells of a boy who promised his older brother that he’d take care of a dog while the brother was at war. The worthless dog gets itself killed by an otter that was protecting its young. The boy decides to hunt the otter in revenge, but over the course of the story learns a valuable lesson about life.

“Command” by James Warner Bellah finishes the book with a patrol by the United States Cavalry. Newcomer Captain Cohill resents his leader, the much older Captain Brittles, who constantly corrects him and makes seemingly irrational decisions. They’re out to find a missing patrol, and find the corpses of it.

Cohill is all for rushing off to find the perpetrators and killing them, but Brittles reminds him that their mission was “find the missing patrol and report back” and standing orders are not to attack Indians that didn’t attack first. A nice touch here is that it’s specified that Native Americans are not monolithic, and that each tribal group has its own customs and habits. (Whether the author is accurate as to these customs is another matter.) At the end, it turns out that Brittles is more sly than he lets on, and teaches command in his own way.

This book does not seem to have been reprinted, so you will have to try your luck at garage sales and used book stores. It’s a solid collection of stories; I liked the Benet and Rogers tales best.