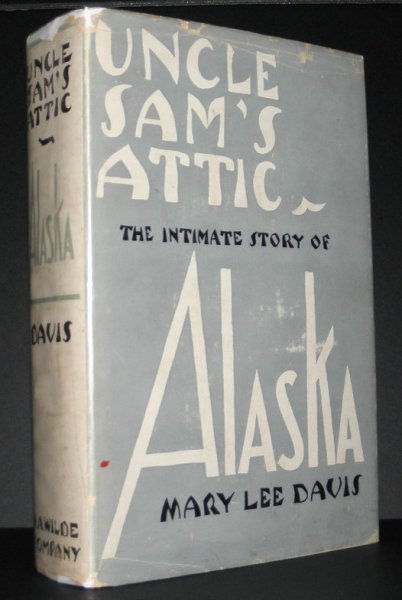

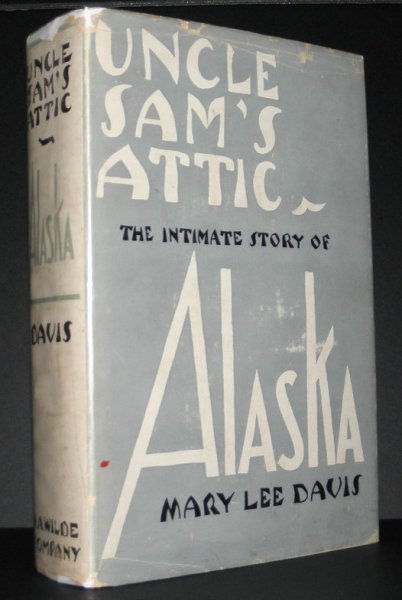

Book Review: Uncle Sam’s Attic: The Intimate Story of Alaska by Mary Lee Davis

There was a time, not so long ago, when Americans knew little about the territory of Alaska. In the popular imagination, it was a desolate land of perpetual ice and snow, inhabited mostly by gold miners and “Eskimos.” Indeed, many people confused it with Canada’s Yukon Territory.

In 1930, then-popular writer Mary Lee Davis wrote this book about her time living in Alaska in the 1920s to help bring people up to speed. Her husband was an inspector for the Federal Bureau of Mines, so they traveled all over the Alaskan territory, with headquarters in Fairbanks. Mrs. Davis combines facts and figures about Alaskan resources with historical background and her personal experiences living and traveling there.

One thing Mrs. Davis is quick to emphasize is that even by the Twenties, the wild frontier days were over. Movie companies looking for dancehall sets had to build their own, because all these staples of the Gold Rush had closed down. The men and women who were there for lawlessness had died or moved on, and Alaskans were now mostly about building a home to live in.

The breezy, chatty writing style works well for most of the book, with the early chapters about how to get to Alaska by ship, and expanding out from there. There are some black and white photographs that give us an idea of what Alaska looked like in those days. Mary Lee Davis charmingly describes her Fairbanks house, which is now a local landmark.

The book is clearly designed to both encourage migration to Alaska, and to convince the contiguous 48 states’ population to support greater connections between the two areas, possibly even statehood. It really does make the territory sound like a beautiful place to live.

The “attic” metaphor, while initially cute, gets run into the ground in the introduction and I shuddered a bit each time it came back up.

There’s a certain amount of colonialist attitude on display here, and some well-meaning ethnic stereotyping. Mrs. Davis repeatedly uses the word “Eskimo” but does point out that this is an outsider word, and discusses the actual native peoples in better detail. She also uses Mount McKinley and Denali interchangeably.

The history of the territory is presented piecemeal and out of order; you may also want to read a more formal history to get things straightened out in your mind.

Still, this is a well-written book, and highly recommended for a glimpse at Alaska in the 1920s.