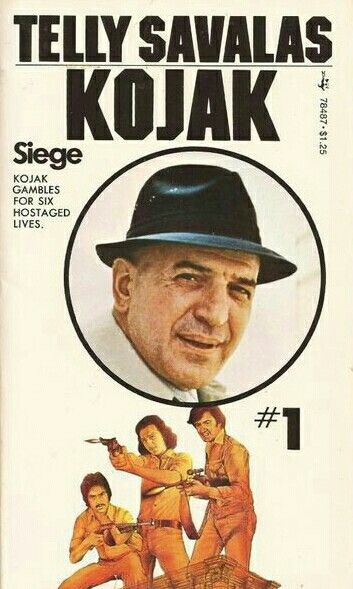

Book Review: Siege by Victor B. Miller from a script by Robert Heverly

The bank robbery itself went smoothly, but the getaway was a disaster due to fast police response. Two of the robbers panicked and drove off with the van, while the other four in the car wound up roadblocked and fleeing on foot. One shootout later, a cop is dying and so is one of the robbers. The remaining three crooks take refuge in Apex Surplus. What it turns out to stock is a surplus of guns and ammunition. The robbers take the owner and customers hostage. Only one police detective has the moxie to end this standoff with minimum civilian casualties. Kojak!

The Kojak television series aired from 1973-1978, a gritty crime drama that was very influential in its day. This book is a novelization of the first episode, “Siege of Terror.” (There had already been a TV movie that introduced the character.)

Theodore “Theo” Kojak (Telly Savalas) was a New York City police detective, a tough guy and incorruptible, but given to a streak of meanness towards suspects and ribbing of his subordinates. He follows procedure, mostly, but isn’t too keen on rules that protect criminals, mentioning in the book that he wishes Miranda had gone into another line of business.

The novel roughly follows the plotline of the TV episode, as Kojak tries various ways to defuse the hostage situation and tracks down leads. As this is a series with a central character, Kojak takes most of the important actions himself where in real life they would be delegated to other police officers. It makes for some tense moments.

But since it’s told in first person, we also get to hear Kojak’s thoughts, including a flashback that explains his rage at this hostage crisis, and also that he’s always dressed snappier than his pay grade. His decision to cut back on smoking takes place later in the series, but we do get a moment where Kojak sucks a lollipop.

On the down side, surprise homophobia! In fairness, while Kojak thinks a slur, he doesn’t say it, treats the gay Hispanic man no worse than any other random civilian, and at the end of their interaction draws a distinct line between the otherwise law-abiding homosexual “citizen” and criminal “creeps.” Which is pretty good for a 1970s NYPD cop who got his badge in the 1950s.

I don’t think this book has been reprinted in years, but it’s worth looking at garage sales if you’re nostalgic about the classic cop show.