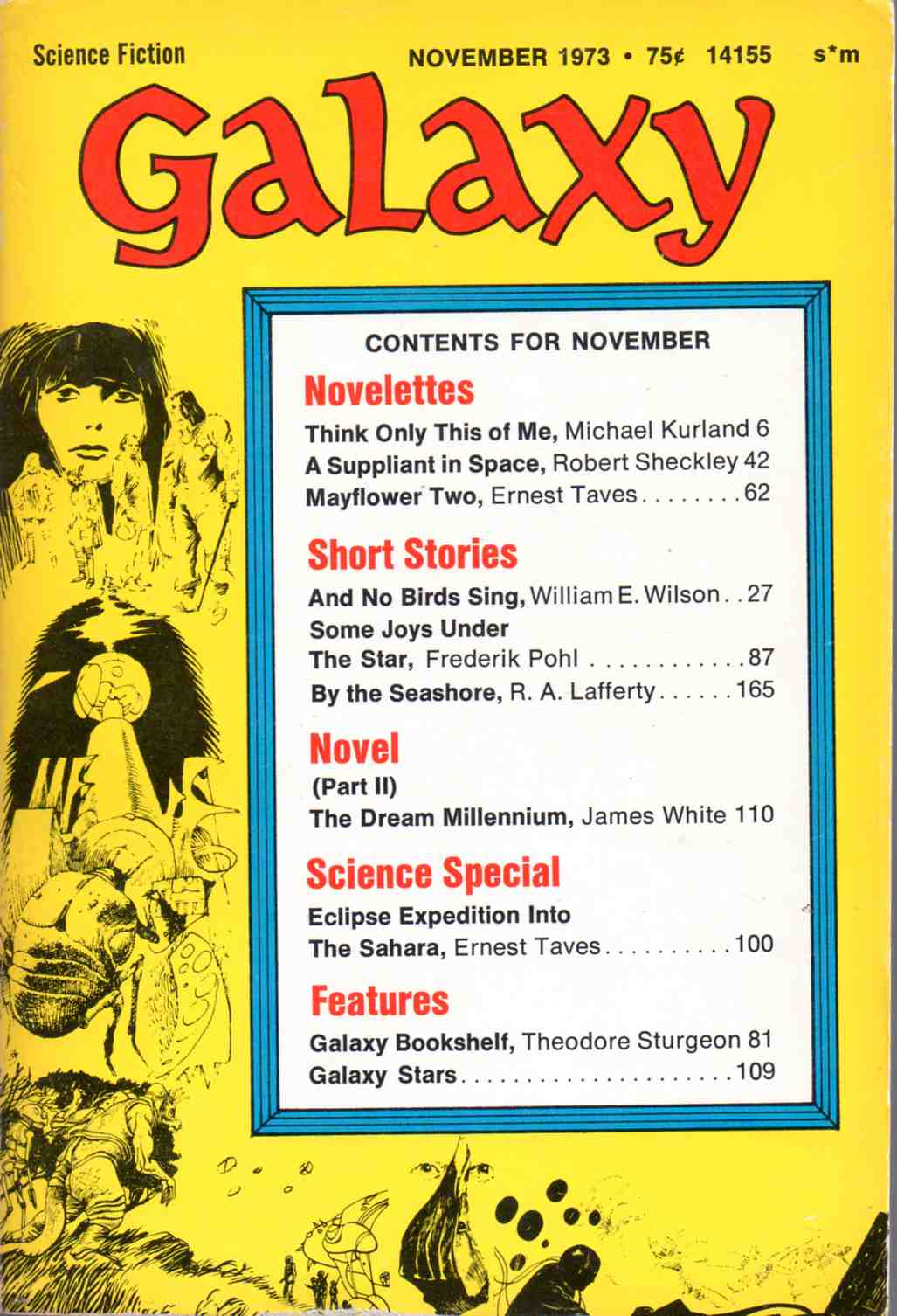

Magazine Review: Galaxy Science Fiction November 1973 edited by Ejler Jakobsson

The last issue of this magazine I reviewed was from the 1950s, so there’s a considerable time gap, and we can see some definite changes in the science fiction field.

“Think Only This of Me” by Michael Kurland opens the issue. Humanity has gone to the stars, and the one thing that Earth is still valued for is its history common to all humans. So Earth has been turned into an enormous history theme park named Anno Domini. There are areas called “Centuries” where the cultures and conditions of notable eras are recreated for the amusement of tourists.

Which, you know, great, but the inhabitants of these Centuries are brainwashed to believe that they’re actually living in those times and strictly controlled not to break the illusion. And there’s no indication that they were given any choice about becoming theme park attractions. I have some serious ethical qualms about this.

But that’s not the focus of the story. Christopher Charles Mar d’Earth is a member of the Parliament of Stars who’s getting burned out at his job, so takes a vacation in Anno Domini. While in the Seventeenth Century, he meets a fellow tourist, Diana Seven. She’s expert at combat, given to philosophical questioning, and well-informed in some areas while being startlingly naive. They become lovers.

And then the story gets icky. It seems that Diana is a genetically engineered super-soldier, who looks twenty due to forced aging, and with the equivalent of an adult education, but chronologically twelve. She’s been put on a long leash by her creators so that she can spend a couple of years learning to interact with more normal humans before going full time as a government operative. Now that Christopher knows her circumstances, what will he do?

A depressing story.

“And No Birds Sing” by William E. Wilson has factory owner Harry Norman visiting an oculist with an unusual vision problem. He’s starting to lose the ability to see people. Things he can see just fine, but people keep fading out. Sometimes it affects his hearing, too. While there turns out to be a science fiction explanation, it’s also metaphorical, or so Harry takes it. This ending is more optimistic, at least in the short run.

“A Suppliant in Space” by Robert Sheckley involves an alien named Detringer who has been exiled to space by his people for crimes against their culture. This coincidentally makes him the first alien contacted by human explorers. But when the humans learn of Detringer’s crimes, will justice be done?

This is a comedic tale, with clashes between the civilian and military commanders of the exhibition, and a hilarious scene of the ship’s captain unleashing the reporters on a potential threat. Justice of a sort is indeed done.

“Mayflower II” by Ernest Taves is set in the very near future (you can tell by the technology) as two married couples are sent to a lunar research station to see if babies can be conceived on the moon. This one’s more about the human drama and the effects that trying for a baby and maybe not succeeding have on people and their relationships. Gets very tense at a couple of points.

“Galaxy Bookshelf” by Theodore Sturgeon reviews four East European SF books, and Robert A. Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love. Mr. Sturgeon appreciates the work of Stanislaw Lem.

“Some Joys Under the Star” by Frederik Pohl has Earth attacked by an alien empire with a device that creates joy to make us unable to fight back when they invade. It doesn’t turn out as they expect. Seventies social and political satire are on display here.

“Eclipse Expedition Into the Sahara” by Ernest Taves is a fact article about the June 30, 1973 solar eclipse and efforts to study it. The highlight of the issue, and recommended for fans of science and the history of science. It comes with a photo spread, and a mini-bio of the author.

“The Dream Millenium” by James White is part two of three. Dr. John Devlin is effectively captain of a hibernation ship seeking out a new planet for the remnants of humanity to live on. He’s spent most of the trip in suspended animation himself, dreaming of past lives (but are they his past lives?) and awakening only for evaluation of prospective homes and emergencies.

Things aren’t going so well. The first few worlds passed by were all unsuitable for one reason or another, the hibernation may be causing mental instability, and it’s beginning to look like the ship won’t last until the projected end of the journey.

Not that the doctor had a bright future at home. Earth had become a dystopia, with male inhabitants divided between gun-toting “citizens” and unarmed “sheep”, while women were essentially property. Constant gun violence and terrorism were the norm. Pollution and overpopulation were certain to lead to total societal collapse in the near future.

This story suffers from being the middle section of a three-parter. Most of this part is taken up with flashbacks to the Earth and an elaborate dream sequence in which a king slowly slides from honor into deceit. However, Dr. Devlin and his love interest Yvonne do find a solution to one of the problems plaguing the voyage.

“By the Seashore” by R.A. Lafferty rounds out the issue with a bizarre tale about a boy who finds a seashell. Or is it that the seashell finds him? This one’s heavy on the quirkiness.

Again, I enjoyed the fact article best, but the Sheckley and Pohl stories were also very good. The Taves is the best of the serious stories.