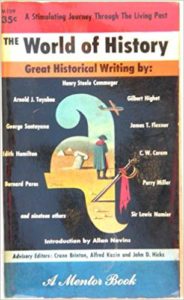

Book Review: The World of History edited by Courtlandt Canby & Nancy E. Gross

History is a very wide and deep subject. It extends from the beginning of the universe (though much before written records is speculative at best) to just this last minute, and from the movements of great nations to what precisely people in Twelfth Century England had for breakfast. There’s more of it every year!

This volume published in 1954 is a sampler of historical writing that was considered relevant and high-quality at the time. There are 24 pieces from already published works, and four from upcoming volumes. It was sponsored by the Society of American Historians, though not all the writers are American.

After a brief introduction by Allan Nevins, the book begins with “Sailing to Byzantium” by Gilbert Highet. He talks about why Byzantium was at the time a relatively less-studied subject of history, and the cycles of civilizations; perhaps America is not yet as mature for its time as Byzantium was?

Each essay has an editor’s introduction that attempts to segue from the previous entry to the new one. Some work very well–others are stretching it.

The final selection is “The Retreat into Isolationism” by Foster Rhea Dulles, on the topic of why America chose not to join the League of Nations. It was as much domestic issues as the fear of foreign entanglements, and policy designed to protect a weak and struggling nation was applied to a strong nation that was increasingly projecting its power outside the borders.

There is a definite trend towards a Christian Anglo-American white male viewpoint, with little of what modern academics would call “own voices” being represented. Thus this book might be most interesting as a time capsule of the historical writing field as it existed in the early 1950s (especially as it talked about recent events, such as Frank Gibney’s “The Japanese Way”, about post-World War Two Japanese society, which was about to undergo massive changes.)

A couple of favorite pieces: “Dinner at Four” by Arnold Palmer (no, not that one) which looks at how the British upper crust came to be eating their meals later and later in the day. (Dinner being here what I’d call “lunch.”) And “Charles Dickens: Social Reformer” by Edgar Johnson, which talks about just that.

“The People’s Crusade” by Steven Runciman is a dry account of exciting events, while “The Young Napoleon” by J.M. Thompson is shot through with gratuitous French, ordinary words and phrases immediately followed with their mundane translations, rather than confining it to a few bon mots.

This book seems not to have been reprinted any time recently, so recommended to the sort of history fan who likes combing used book stores and rummage sales for one-offs and odd pieces.