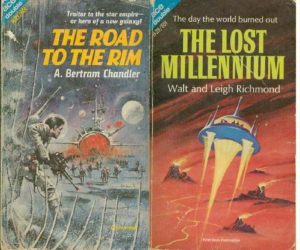

Book Review: The Lost Millennium by Walt & Leigh Richmond | The Road to the Rim by A. Bertram Chandler

It’s time, again, to review an Ace Double, one of those formats so dear to my youth that has since vanished.

The Lost Millennium has as its frame story an engineer being approached by an archaeologist about his latest project, a “solar tap.” If the upcoming experiment works, and the tap can be built, it will be able to use the Earth as a gigantic electromagnetic engine, providing near-infinite broadcast power for humanity. Of course, there’s the potential for disaster, but that’s why the experiment is taking place in the middle of the desert far from civilization.

The engineer’s answers to the archaeologist’s questions confirm the second man’s hypothesis, as he had suspected when he first read of the solar tap. As the archaeologist explains, he’s been following clues in the world’s religious texts and legends, and he is now convinced that the solar tap has existed before, which explains everything. Pangaea, the Great Flood, flying carpets, the Pyramids, domestication of cats and dogs, UFOs, everything!

The archaeologist then spins a tale of Earth’s first human civilization, with its advanced technology and eventual doom.

This 1967 novel fits nicely into the speculative fiction trend of explaining ancient mythology and/or history using science fiction tropes. In this case, primarily but not exclusively the Book of Genesis. Lord Dade Ellis is a master of molecular biology who commissions a huge submarine as an experimental base, and after the solar tap goes horribly wrong, rebuilds humanity and the animals from the specimens aboard this vessel. Other obviously named characters supply more of the ancient secret history.

Unlike Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods, which would come out the following year, in this book the ancient astronauts are Earth humans from the super-advanced civilization who’d managed to get off the planet in starships before the solar tap catastrophe, and returned afterwards to help rebuild and guide the new civilizations. (Not without some bumps, as hinted by “Luce of Pharr.”) Much of this part is inspired by the work of Immanuel Velikovsky in Worlds in Collision, but without the “Venus is a part of Jupiter that erupted out” silliness.

The book concludes with the newly-enlightened engineer considering the building of starships so that Earthlings can meet their long-lost cousins on an even field.

While drawing on pseudoscience that was popular back in the day (and in some circles is still at least considered), most of the speculation in this book is contraindicated by scientific discoveries made since the 1960s. As such, the vignettes of ancient civilization are cool worldbuilding, but the lack of character growth or more than superficial characterization makes this a book not to be sought on its own.

The Road to the Rim is more lastingly relevant, as it’s tied into the “John Grimes: Rim Worlds” series of books. This is the first of the stories by internal chronology, featuring an Ensign Grimes just graduated from the Federation Survey Service academy and shipping out to his first assignment.

As it happens, there are no military transports headed that way, so Grimes ships aboard a civilian merchantman, the Delta Orionis. While in transit, Grimes meets his first Rim Worlders, the disgruntled engineer Baxter, and the lovely purser Jane Pentecost. There’s some politics involved, as the Rim Worlds are independent of the Federation, but not allowed to have their own space navy because the Federation supposedly protects them. In reality, the neighboring Duchy of Waldegren regularly preys on Rim shipping in thinly veiled piracy.

The captain of the Delta Orionis warns Grimes against getting too close to Miss Pentecost as she is rumored to be working as a recruiter for the potential Rim Worlds Navy. But it’s the captain himself who decides to go rogue when the DO finds a ship that has just barely survived an encounter with pirates. Our captain knows that his ship is carrying weapons meant for the Survey Service, and has a plan for turning the crippled merchantman into a Q-ship and baiting the pirates into a trap.

Ensign Grimes quite rightly objects, and is placed in the brig so that his career will not be tainted. But after Jane gives him a pity lay, Grimes decides that he’s in love with her, and joins the Q-ship crew.

The good: Mr. Chandler, a long-time merchant mariner himself, really “gets” the sea-going mindset and “space as an ocean” setting. There’s considerable suspense and some good action scenes. This story explains where Grimes gets his “Liberty Hall” catchphrase from.

The less good: The future depicted is kind of sexist, the few female military officers Grimes has met are dismissed as “equine” and on the Delta Orionis the female crewmembers work in accounting and entertainment. There’s prejudice against the psychic “radio” operators for being “spooky,” which is never called out in the story as a bad thing.

The ugly: Grimes persistently bugs Jane for more sex, refusing to take “no”, “hell no” and “absolutely not” as answers, even when she gives reasonable reasons why she won’t. Only when Grimes learns Miss Pentecost is now going steady with someone who outranks him does he finally desist. (He and the other man get a chuckle out of the situation.)

Recommended to fans of Mr. Chandler’s other work who can forgive the sexual harassment subplot.