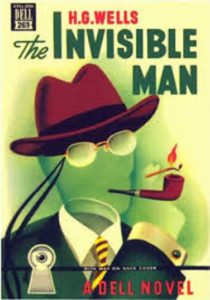

Book Review: The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells

The sleepy village of Iping doesn’t get many visitors in the middle of winter, so when Mrs. Hall gets a new customer (and one that pays on time!) for her boarding house, it’s not polite to look a gift horse in the mouth. It’s true the guest is something of an odd duck. He keeps himself fully clothed and bandaged at all times, and wears dark glasses, performs mysterious chemical experiments in the parlor, and has a nasty temper. But the stranger (odd, I don’t think he ever gave a name) keeps to himself and, again, pays on time.

But as winter melts into spring, the little oddities of the stranger begin to rub people the wrong way. Plus, there are some mighty weird events in the village. And the guest appears to be running out of money, so Mrs. Hall is running out of patience with his eccentricity. After the vicar and his wife are robbed by an unseen criminal, the stranger suddenly has money–could there be a connection? The Halls decide to have it out with their boarder once and for all–but they could never have guessed his secret!

The power of invisibility and its potential abuses have been the subject of fanciful stories since time immemorial. This 1897 novel has one of the first truly thought-out considerations of how one might become invisible and the consequences thereof. Griffin, the Invisible Man, is not so much invisible as transparent, having found a way to alter the refractory properties of human flesh, blood and bone. He started out as an albino, so didn’t have to worry so much about the pigmentation of skin or hair. His eyes are partially visible, so that he can see.

Griffin claims that he can treat cloth to make it invisible, but never actually does so, requiring him to run around in the nude for much of the story, a nasty handicap in inclement weather. While the Invisible Man is certainly a threat on an individual level, his dreams of rulership require him to have visible accomplices. Unfortunately for Griffin, his choices of lazy tramp Thomas Marvel and old schoolmate Kemp both backfire.

While it’s suggested that either the formula itself or the permanency of his invisible condition have driven Griffin insane, it’s also clear that he was not the most stable of scientists before his transformation. When his job as a poorly-paid college demonstrator (TA) prevented him from pursuing his experiments with optics, Griffin had no hesitation in stealing money from his father. Griffin has no qualms when the old man commits suicide, only annoyed that he must set aside time to go to the funeral. Griffin is bigoted even by the standards of his time, quick with ethnic, gender-based, and ableist slurs, and is cruel to a cat.

Kemp is quick-witted, and intelligently tries to stop Griffin before the Invisible Man can escalate his reign of terror. (But it’s too late for the one man Griffin definitely murders as opposed to probably murders.)

There’s quite a bit of incidental humor in the story. My favorite bit is the visiting American who just happens to be carrying a large firearm and starts shooting randomly in the direction of the Invisible Man, apparently in the belief that sufficient firepower can solve any problem. (In fairness, he does manage to wing Griffin.)

Those more familiar with the movie versions might find the long early section before the big reveal dragging. Still, it’s a classic for a reason, and the last section is genuinely suspenseful.

Recommended to science fiction and horror fans who enjoy stories of invisibility.

And here’s Claude Rains as Griffin: