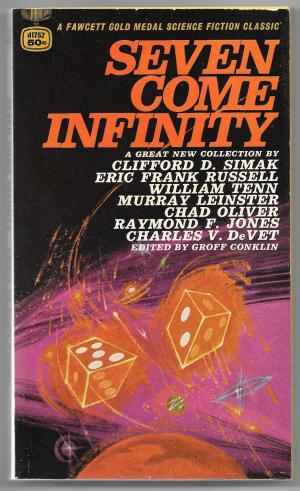

Book Review: Seven Come Infinity edited by Groff Conklin

The title of this anthology refers to the phrase “seven come eleven” from craps, referring to the ways you can win. In the preface, it’s mentioned that there are a finite number of possibilities for the outcome of rolling two dice. But when you write a story speculating on the future, the possibilities are infinite. Will these seven stories be winners?

“The Golden Bugs” by Clifford D. Simak starts us off in 1950s suburbia. An insurance salesman is living a reasonably comfortable life with his wife and son, but there’s that one neighbor he hates. It’s an engineer that is building a robot orchestra in his home and insists on testing their musical abilities first thing in the morning. Also, our protagonist’s house has a bug problem.

This is not the first time he’s had an insect incursion (the grease ants have been a recurring issue) but this is most assuredly the weirdest. The little golden critters look like nothing on Earth (according to the retired entomologist next door.) At first, they’re mildly annoying, then turn helpful…and then scary.

The golden bugs are nicely alien, and their motives are never clear, only their actions, which may or may not have anything to do with their attitude towards humans. The threat level multiplies as we learn more about the bugs’ capabilities. There’s a comedy twist when the protagonist figures out a plan to deal with the bugs that might have worked, but the music-loving neighbor puts his better plan into operation first.

“Special Feature” by Charles V. DeVet opens in Saint Paul, Minnesota, as a murderous alien infiltrates the city one winter night bent on mayhem. She’s confident the stupid humans will be easy prey as she learns to fit in and kill her way to the top. What she doesn’t know is that she’s already been caught on camera.

And that’s where the story gets interesting. For in this future, the surveillance society is not run by the government, but by the entertainment companies. There are cameras nearly everywhere in the city that can be operated remotely, and content providers scanning for anything they can sell to the networks. Vern Nelson is one of those workers, and he spots the alien before it makes its first attack. He realizes how exciting this will be and gets exclusive rights to make a reality show of it.

For the rest of the story, we watch Pentizel as she cleverly figures out how to pass for human (at least from a short distance) and schemes to conceal her presence from the locals as she picks them off. We also watch Vern as he finds ways to exploit Pentizel’s actions to attract an audience (and advertiser dollars) without ever letting her know her every move has been watched. (Well, almost every move. The broadcast standards people decide that even if it’s an alien, “no bathroom stuff.”)

Eventually, the authorities decide that ratings or no, Pentizel has killed once too often (that is, someone who isn’t a homeless person or a criminal) and the show must end. Vern has to find a way to finish the program with a bang!

Television was still in its early days when the story was written, but in some ways it’s eerily prescient. Suitably updated, it’d probably make a great movie.

“Panic Button” by Eric Frank Russell concerns an Antarean exploration mission looking for new inhabitable planets. They’ve found one, the problem being that there’s an inhabitant, an Earthman. And he’s already pushed the big blue button on the wall.

The situation is pretty transparent to the savvy reader, but the fun comes from the aliens debating over what they’re going to do each time new information comes in, and their contrasting personalities.

“Discontinuity” by Raymond F. Jones is about a new experimental process of computerized brain repair. Among other things, it uses the memories of people who know the patient to help rebuild the parts of the brain related to those relationships. Unfortunately, everyone who’s been treated by the process, while now able to get along physically, is completely aphasic, unable to communicate or understand communication.

When the inventor of the process suffers massive brain damage as the result of a murder attempt, he’s subjected to the process (over the objections of his wife, the attempted murderer) in a last-ditch attempt to perfect the operation. He, too, emerges aphasic.

However, unlike previous test subjects, Dr. Mantell is not immediately restrained, and is able to escape. He soon discovers that his mind is functioning just fine, other than being completely unable to understand human language (including gestures.) Then he meets other escaped subjects and learns that he can communicate with them.

Dr. Mantell realizes that they have in fact become hyperrational superbeings, and the reason they no longer understand human communication is because it’s inherently irrational enough that their refined minds are no longer able to handle it. In order to survive, they will need to find a way to, well, dumb themselves down to talk to the humans.

This story uses the “10% of the brain” thing, though not by name. More annoyingly, it uses the cliche common in Fifties SF of “wife of scientist that doesn’t understand or care about science and is therefore horrible to him.” To the writer’s credit, Dr. Mantell realizes (now that he’s hyperrational) that he was a total jackass to her himself and is equally responsible for the failure of their marriage.

The story ends on a pro-transhumanist message, as an ordinary human begs to be the next one uplifted. Chilling if you’re not into hyperrationality as the next step in human evolution.

“The Corianis Disaster” by Murray Leinster concerns the title starship, stuffed to the portholes with planetary dignitaries (and one physicist), which has an accident with its faster than light drive. It takes a couple of hours to replace the burned out parts, so the ship is late to its destination. Or is it? It seems that the Corianis landed a couple of hours ago.

Each ship appears to be identical to the other at first, right down to the passengers. (With the exception of physicist Jack Bedell, who is not duplicated.) Since the appearance of these doubles might be the work of sinister forces, neither ship’s personnel are allowed to disembark.

Most science fiction fans will realize what happened immediately, but Mr. Bedell takes much longer, and none of the civilians ever grasp the truth before he finally kind of sort of explains it towards the end. They’d rather believe in evil alien shapeshifters, or witches. It doesn’t help that Mr. Bedell seems incapable or unwilling to put things in layman’s terms.

This is another one where Fifties social norms date the story. Women are wives, nurses and secretaries, not government officials or scientists. Mr. Bedell’s love interest is a secretary who doesn’t get what he’s talking about but can tell he’s the only sane man aboard.

“The Servant Problem” by William Tenn starts “This was the day of complete control…” and ends “THIS WAS THE DAY OF COMPLETE CONTROL.” In between, we meet Garomma, the Servant of All, the humble dictator of the world. He enjoys thinking about how he has domesticated the entire human population into thinking he serves them instead of the other way around. Then we pull back a bit to meet the man behind the man. And the man behind the man behind the man. And….

It’s a fascinating look at social power structures, and how systems become self-sustaining.

“Rite of Passage” by Chad Oliver rounds out the book. Three survivors of a plague ship take a shuttle down to the nearest planet. The natives appear primitive, but are reasonably friendly. One of the survivors, an anthropologist, realizes that appearances are deceiving and the local culture is far more complex than it first appears. Also, there’s evidence the plague survivors aren’t the only technologically advanced visitors around.

This fits into the category of Utopian fiction more than anything else, as the Nern society turns out to be better than the visitors’ in just about every way. (Think the civilization version of that Japanese decluttering method.) Lots of infodump towards the end.

I liked “Special Feature” and “The Servant Problem” the best. “Rite of Passage” is a little too taken with its message for my tastes.

This volume does not seem to have been reprinted past 1967, but some of the stories may have been collected in more recent books. Keep watching garage sales!