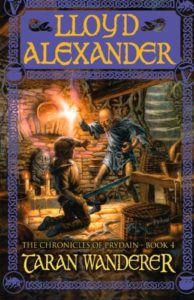

Book Review: Taran Wanderer by Lloyd Alexander

With the Black Cauldron destroyed, Death-Lord Arawn has retreated to his own lands for the time being, and no other major threats beset the realm of Prydain. Long peaceful days at Caer Dallben have given Taran Assistant Pig-Keeper time to think. Taran has realized a number of things, including that he wants to be together with Eilonwy for the rest of their lives…and that he has no idea who he is.

That’s both in the metaphorical and literal sense. Taran has no idea who his parents were, or if he has living kin. And his life at Caer Dallben has been more about caring for the oracular swine Hen Wen than discovering his own way of life. What if he is of noble birth? What if he is truly a peasant? Can he be together with a princess if his birthright is unknown?

Dallben the enchanter is as usual not a great deal of help; he either cannot or will not tell Taran the details of the boy’s heritage. So it is that Taran sets out with his faithful companion Gurgi to the Marshes of Morva. There, Taran consults the three dangerous sister enchantresses, but learns he cannot pay them a price high enough to learn his own secret. They do, however, mention that the Mirror of Llunet might give him a glimpse of his true self.

Lake Llunet, where the Mirror was last seen, is clear at the other end of the country, and the rest of the story is about Taran’s journey there.

This is the fourth of five novels in The Chronicles of Prydain, a children’s series based loosely on Welsh mythology. (Mr. Alexander mentions in the foreword that he’s borrowed bits from other folklore as well.) The focus is on Taran’s character development, so there’s no one overwhelming threat, but a number of smaller problems and lessons that Taran must overcome or learn from on his way to maturity.

Indeed, Taran has grown a great deal from the callow lad he was at the beginning of the series; he shows wisdom whenever he thinks about how to help others, rather than his own problems. But he still needs to let go of the notion that he needs to be special before he can embrace his true destiny.

Not everything is hard lessons; not-quite-human Gurgi and the prevaricating bard Fflewddur Fflam provide comic relief. But there are villains as well, the terrifying Morda, who cannot be killed by mortal means (and who is responsible for some of the mysteries in earlier books) and the greedy mercenary Dorath. Eilowny does not appear, but is often mentioned.

The book is well-written, though some of the running character tics grow tiresome by the end. (And the lesson at the end is obvious at the beginning if you’re at all familiar with children’s literature.) It’s a good breather before the climactic events of the final volume, where Taran and Eilowny must take their mature roles.

I recommend the entire series, and the Disney version has its good bits as well.