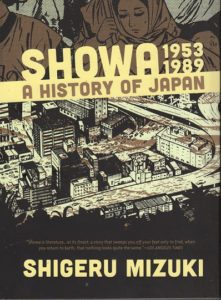

Manga Review: Showa: A History of Japan 1953-1989 by Shigeru Mizuki

This is the final volume of Shigeru Mizuki’s history of Japan and his personal life during the Showa Era. It mixes events that affected the entire country with stories of his struggles as a man and an artist.

As noted in the introduction by Frederik L. Schodt, this volume covers more time than the previous three put together. It covers Japan’s transition from a militarized country reeling from utter defeat, to a nation that was all about business. Many of the events covered will be new to American readers (though manga and anime fans may see the roots of certain storylines in real life happenings.)

The book also chronicles the long years of poverty Mizuki endured as he struggled to earn a living as an artist. Again, this is a warts and all portrayal, so we learn that his arranged marriage was by no means a love match, but something his parents insisted on. Even when Mizuki finally makes it big with a hit manga, he learns that success is its own trap. Now that people want his product, he has to keep putting it out on strict deadlines bang bang bang.

I learned a lot. For example, while it’s been retrofitted into many historical dramas, kidnapping for ransom was a new crime in 1963, made possible by rising prosperity meaning rich people had enough cash to pay ransom. The “paradox of prosperity” is discussed: As rising prosperity made the inside of people’s houses more comfortable, the associated pollution made the outside of their houses less comfortable.

As Mizuki’s personal star rose, he had to take on assistants to help him produce all the work he was now obligated to put out. Some of these assistants, like Ryoichi Ikegami, went on to become famous manga creators in their own right. Others…did not. A subplot in one chapter has an assistant vainly attempt to get his original work published to impress a potential marriage partner.

A couple of chapters are dedicated to daydreams Mizuki had, one where he takes a vacation to the afterlife, and another where he contemplates a company that facilitates extra-marital affairs (and admits that his long-suffering wife might also appreciate the idea.) In real life, he reconnects with the New Guinea natives that had befriended him decades before.

The volume ends with a completely transformed Japan, and Mizuki’s wish that while the future is yet unwritten, the new generations will learn from the mistakes and suffering of the past. Mizuki lived on into the second decade of the 21st Century, still working up until the end.

Once again, the primary narrator is Nezumi Otoko (Rat Man), and we meet the real life person who inspired his personality. One chapter is instead narrated by a traditional storyteller who mentored Mizuki for a while. Readers who are unused to manga conventions may find the art shifts uncomfortable.

In addition to the standard footnotes and endnotes, this volume ends with a number of color plates that demonstrate Mizuki’s art at its most detailed. this is great stuff.

There’s some uncomfortable bits, including rape, cannibalism and suicide. There’s also some toilet humor (which at one point turns dramatic.)

Like the other volumes in the series, a must have for manga and anime fans who want to know more about Japan’s recent history. It would also be good for more general history students seeking a new viewpoint. Highly recommended.

1 comment

Comments are closed.