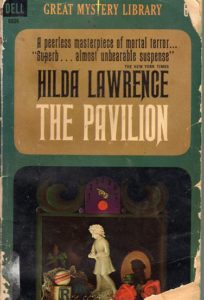

Book Review: The Pavilion by Hilda Lawrence (also published as “The Pavilion of Death”)

When Regan Carr’s mother passes away from illness, the young woman is hard-pressed. Her part-time job as a small town librarian for $25 a week (roughly equivalent to an $8/hr job in 2017) is not sufficient to cover the doctor’s bills and other expenses of her mother’s final days, let alone allow her to live in any sort of comfort. So when a letter arrives from her distant (and wealthy) cousin Hurst Herald, asking her to live with him, Regan decides to give it a try.

But when Regan arrives with her meager possessions, Hurst Herald is dead. And he evidently hadn’t told the rest of the family she was coming, so the relatives view Regan with suspicion. There are those who seem glad to see her; Miss Etta, a kleptomaniac pensioner who was an old friend of Hurst’s, and the Crain sisters, elderly maids who appreciate Regan’s kindness. The relatives warm up a bit when she proves her arrival was expected, and Regan is given an out-of-the-way room for the moment.

This novel is in the Southern Gothic tradition, featuring a dysfunctional family with dark secrets living in a fine mansion that is beginning to decay. It’s a slow burn in many, many ways–it’s halfway through before Regan realizes that the family’s history of tragic accidents doesn’t include any actual accidents. Much depends on her suppressed memories of what happened in the pavilion out back of the house during her childhood visit.

Regan is a petite woman, who looks even more childlike than her age of twenty-two. A running gag is her bunny slippers, a rare splurge purchase for the poverty-stricken lady. In a more action-packed story, she would be the damsel in distress type, but the menace here is more subtle, hidden between the lines of seemingly innocuous conversations.

The slow burn serves the story well most of the way through. There’s a particularly chilling scene where one character’s previously comical behavior is revealed to be the result of psychological abuse as a child. This does, however, mean that the last chapter needs to wrap everything up in a bit of a rush, with the murderer’s identity confirmed by elimination in the final paragraphs.

The viewpoint is mostly Regan’s, but we do have moments seeing the thoughts of other characters. For example, one of the maids daydreaming about working for a less strict employer so she wouldn’t have to set her alarm clock an hour ahead to keep her job, and worrying every day that they will notice the difficulty she has getting up the stairs. (Towards the end she talks about her and her sister’s fear of ending their days in a charity ward.)

There’s a touch of period racism; the family has no black servants because (the housekeeper thinks) they’re superstitious and don’t react well to summons from empty rooms. African-Americans appear in scene descriptions, but none are relevant to the plot.

This is an atmospheric book that will reward the patient reader. My 1960s copy is in rough shape; you might be able to find the 1980s reprint in better condition.