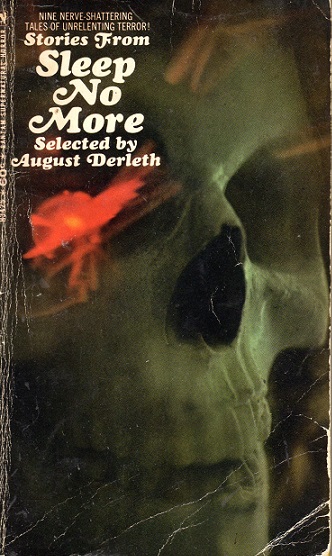

Book Review: Stories from Sleep No More edited by August Derleth

Sleep No More was a 1940s anthology of horror fiction put together by noted Wisconsin historical fiction (and horror) author August Derleth. It featured primarily creepy stories from the pulp magazines of the 1930s. In the 1960s, a paperback reprint came out. To make it a manageable size with the binding limitations of the time, only the first nine stories were included; and presumably there would have been a sequel with the rest had sales justified it.

“Count Magnus” by M.R. James leads off with the tale of a would-be travel book writer who visits Sweden and wakes up something that should have been kept sleeping. Like many tales from the era, it’s told at a remove, reported by someone who found the protagonist’s papers and pieced together the story from them. That aside, it’s an excellent example of horror by implication–none of the presumably gory bits happen on page, and the results are not directly described. The moment of most terror is a lock that should not be open being open.

“Cassius” by Henry S. Whitehead is set in the West Indies. A man who’s had an ugly growth removed is hunted by a small but deadly enemy. It starts well, but the explanation for the terror is heavily racist, involving some dubious genetics and “race memory.” Also, the ending is an anticlimax.

“The Occupant of the Room” by Algernon Blackwood is the oldest story in the collection. A schoolteacher who altered his holiday plans on a whim finds himself at a Swiss inn with no vacancies. Wait, there is one room, but the catch is that the occupant just vanished a couple of days ago–they may or may not be returning. The room’s atmosphere is oppressive, leading to thoughts of suicide. Unnatural thoughts!

“The Return of the Sorcerer” by Clark Ashton Smith has a desperately unemployed man (who happens to know Arabic) get a job as secretary to reclusive scholar John Carnby. Carnby turns out to be an occultist with eccentric habits, and a fear of leaving his room at night. Supposedly, the noises in the halls are rats, but the glimpses the secretary gets don’t look like any rats he’s ever seen. Mr. Carnby needs some passages from the Necronomicon translated at the highest priority, passages about sorcerers being able to come back from the dead. The job does not end well.

“Johnson Looked Back” by Thomas Burke is a rare second-person story. The reader is addressed as though they were Johnson, who is pursued by a mysterious blind, handless man. The narrator urges Johnson not to look behind him, but of course he does and dooms himself. The ending is kind of kludgy, suggesting the whole story is a metaphor.

“The Hand of the O’Mecca” by Howard Wandrei is set in Minnesota, not far from Mankato. Finnish-American farmer Elof Bocak is crossing the fields at night to woo his neighbor, Kate O’Mecca. Perhaps he should have paid more attention to the superstition about bats on the ground. Some nice local color, but the twist is telegraphed.

“‘He Cometh and He Passeth By!'” by H.R. Wakefield concerns a barrister named Edward Bellamy. He’s contacted by an old school friend, Philip Franton. They’d fallen out of touch after the War, but now Franton is in a spot of trouble. It seems he was for some months host to Oscar Clinton, a fascinating fellow who Philip was quite entranced with initially.

Eventually, Clinton’s less appealing habits (impregnating chambermaids, stealing and forgery) became unbearable, and Franton broke ties with the man. Some time later, Clinton tried to use his “friendship” with Philip as a recommendation to a club, and the wealthy man blackballed him. Clinton was not well pleased, and sent Franton a supposedly cursed image. Now Philip is jumping at oddly shaped shadows.

Bellamy is unable to prevent his friend’s horrible death, but perhaps he can get a little extrajudicial revenge?

Oscar Clinton is cartoonishly decadent. To quote:

“I fancy,” said Clinton, “that you are perplexed by the obstinate humidity of my left eye. It is caused by the rather heavy injection of heroin I took this afternoon.”

It’s probably meant to evoke the image of the notorious “Wickedest Man in the World” Aleister Crowley. While Clinton only mentions sex with women, there are homoerotic undertones in his relationships with Franton and Bellamy. His comeuppance is satisfying.

“Thus I Refute Beezly” by John Collier is titled after Samuel Johnson’s famous rejoinder to Bishop Berkeley. “Small Simon” Carter is a friendless child who spends most of his time in the garden, playing alone. He claims to be playing with a “Mr. Beezly” who is hard to describe, and no adult has ever seen.

Small Simon’s father, who insists on being called “Big Simon”, is a dentist with some odd ideas about parenting. Big Simon is big on science and fact, and when Small Simon won’t admit that Beezly is imaginary, decides to punish the lad. That’s a mistake.

This story is more often reprinted than most in this collection, and there’s analysis of it at various websites. What struck me was that the author is being snotty about “modern” parenting methods of the sort where parents insist on children calling them by first name. “See? This fellow is all ‘progressive’ and such, but when logic fails, it’s back to corporal punishment just like normal folks!”

Rounding out the collection is “The Mannikin” by Robert Bloch. A schoolteacher picks a random isolated town for vacation, only to discover that this is the hometown of his old school friend Simon Maglore. In the time they’ve been parted, the deformity of Simon’s back has gotten a lot worse, and the superstitious locals shun him. The basic twist is the same as “Cassius”, minus the racism. Some Lovecraftian references in this story, too.

Most of these are good if dated stories; “Cassius” is the only one that has become outright uncomfortable to read due to its attitudes. While it’s long out of print, the paperback edition should be relatively easy to find in finer used bookstores.