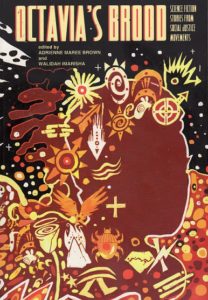

Book Review: Octavia’s Brood edited by Adrienne Maree Brown and Walidah Imarisha

One of the many uses of science fiction is to talk about current issues in a speculative setting. One can posit a world in which current trends have become exaggerated to dystopian levels, or where a solution has been found to a current problem and what that would result in, or imagine how a change in the past would affect an issue…or even just go the allegory route by, say, having anti-Martian prejudice stand in for anti-immigrant prejudice of the current day.

This anthology is dedicated to science fiction stories on the theme of social justice issues. It’s dedicated to the memory of Octavia Butler (1947-2006) a Hugo-winning author of works that touched on such themes as racism, alienation and the environment. There are twenty stories and two essays by a variety of experienced and first-time authors.

The first story is “Revolution Shuffle” by Bao Phi. Two Vietnamese-American young people in the middle of a zombie apocalypse are about to liberate an internment camp for Asian and Middle Eastern-descended people. It seems that in this future, the zombie infestation was declared a terrorist attack, and the most likely suspects were locked up in special facilities to maintain zombie-attracting pistons “for their own protection.” It reads like the first chapter of a YA dystopia novel.

The last fictional story is “children who fly” by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. It’s a future starring her daughter in a globally-warmed Oakland, trying to preserve what’s left of the community through group disassociation. “Evidence” by Alexis Pauline Gumbs also uses heavy author insertion in foretelling a future where material goods are no longer important but personal growth is.

Several stories are clearly in the Afrofuturism mode, such as “Lalibela” by Gabriel Teodros, about a time-traveling Ethiopian king.

The most stylistically interesting piece is “Sanford and Sun” by Dawolu Jahari Anderson, which is a script format tale about junk dealer Fred G. Sanford encountering cosmic funk musician and philosopher Sun Ra. It’s a neat concept, but the “jokes” reminded me of just how much Redd Foxx’s comedic delivery skills carried the Sanford and Son show. Without specifically imagining him in the role at all times, the lines fall flat.

Some of the stories feel like incomplete fragments. “Aftermath” by LeVar Burton (about an African-American scientist developing a cure for Parkinson’s Disease, only to be kidnapped by people who want to skin her alive) and “Fire on the Mountain” by Terry Bisson (an alternate history where the Civil War went very differently indeed) are open about this as they are previews of longer books. Others come off as essays more than stories.

Of the stories in this volume, the one I liked best was “The Long Memory” by Morrigan Phillips. It takes place in an archipelago where people known as Memorials can access the memories of the Memorials who have come before them, back to the beginning of their line. These Memorials have become an important part of the society as the rulers must consult them and their knowledge of history before each important decision.

A wealthy and ambitious politician has become an enemy of the Memorials for reasons including the fact that they remember his ideas turn out badly. He manages to get enough of the government on his side to imprison the Memorials.

The protagonist organizes a hunger strike in an effort to bring the politician to the negotiating table (and also to remind the people that the Memorials have been locked up.) She naturally wants herself and her colleagues to be freed, but also comes to the realization that the people of the Archipelago have leaned on the Memorials for long-term memory so much that they’ve lost the capacity to remember history for themselves.

The essays are “Star Wars and the American Imagination” by Mumia Abu-Jamal, which is about pretty much what you’d think, and “The Only Lasting Truth” by Tananarive Due, which is about Octavia Butler herself, her work, and her legacy.

There’s also a foreword, introduction and outro discussing the themes and importance of the works included, and a set of author bios.

This collection is “important” more than “good”; the quality of submissions is uneven, but they are nevertheless interesting to read and contemplate, and I look forward to seeing the future work of many of these authors. If you have an interest in social justice themes or Afrofuturism, please consider picking this book up.