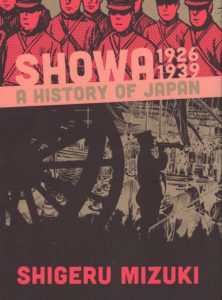

Manga Review: Showa 1926 1939 a History of Japan by Shigeru Mizuki

This is the first volume of Shigeru Mizuki’s massive history of Japan during the reign of Emperor Hirohito, the “Showa Era,” It was a long reign, covering most of the Twentieth Century, from 1926-1989. In addition to the larger story of Japan, it is also his autobiography, as Mizuki’s earliest childhood memories coincide with the beginning of that era.

This volume opens several years earlier, with the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 which devastated Tokyo. The repercussions of this, combined with fiscal mismanagement, created a financial crisis that crippled Japan’s economy. The optimism and liberalization of the Taisho period took a huge hit. Japan struggled along until 1929 and the worldwide effects of the Great Depression hit.

A combination of the Red Scare (the belief that Communists were about to take over), military successes and government incompetence led to the rise of right-wing organizations, especially military cliques. Japan became ever more aggressive against its neighbors in Asia, setting up the puppet state of Manchukuo and grabbing ever more territory from China.

Japan became a rogue state, leaving the League of Nations when that body attempted to intervene in its conquests. Only Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy recognized Manchukuo, and Japan’s alliance with those nations was about to drag it into World War Two.

This is a “warts and all” history, which covers events that many Japanese schoolkids might not be taught in official classes, or have glossed over for them. There are many painful topics in here, so despite childish hijinks in the parts dealing with Shigeru’s early life, I would recommend it for senior high school students and up.

Warts and all is also how Mizuki depicts himself as a child and young man. Naturally athletic but lazy, bright but unmotivated, sensitive but engaging in fights both as part of a gang and solo. It will take the horrors of war (as depicted in the third volume) to force him into a responsible adult life. Perhaps he got some of it from his father, who is shown as a Micawber-like optimist despite his economic woes.

There’s a lot of names and dates, so the end-notes are very helpful–you still might want to have Wikipedia open to assist with some of the more obscure bits and to cross-reference what else was going on in the world at the time. Some bits come across as very dry, making the personal stories a relief.

The art may be jarring for those unused to Mizuki’s style; many pages are drawn directly from photographs in a realistic style, while others are done in a very loose, cartoony fashion. It’s also kind of weird to have Nezumi-Otoko (Rat-man) as the narrator of the more serious history portion-he would not seem the most reliable of narrators.

Overall, not as interesting as the third volume, which features Shigeru’s most harrowing experiences, but well worth seeking out from the library.