Book Review: One in Three Hundred by J.T. McIntosh

Most of you will have run into some variant of the “Lifeboat Problem” at some point. (In my youth, it was done with bomb shelters due to the strong possibility of atomic war.) A disaster has occurred, and a large number of people are going to die. There is one ticket to safety, but only a limited number of spaces available. As it happens, you are the person put in charge of filling those spaces. Here’s a list of people longer than the number of available spots, tell us who lives and who dies. Usually, some choices are easy (the person with vital medical skills lives, while the banker dies because seriously no one cares about money right now) but other decisions are more difficult (your beloved granny who’s partially disabled or the hot woman who dumped you in college but has many good years left?)

And that’s the starting dilemma of this book, originally published as three novelettes in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science-Fiction in 1953. The first section, “One in Three Hundred” reveals that in the very near future, the sun is about to become hotter, making Earth uninhabitable. However, this will also raise the temperature of Mars to the point it will be barely livable. In the limited time left before this insolation happens, the governments of Earth have pooled their resources to build a fleet of ten-passenger “lifeships” to allow approximately one in every three hundred Earthlings to have a shot at joining the small scientific colony already on Mars.

Bill Easson is one of the Lieutenants chosen to pilot a lifeship, and to pick the ten passengers that will be on board. For this purpose, he’s been sent to the small Midwestern town of Simsville. He wastes no time drawing up a preliminary list, but as the deadline approaches, the small-town tranquility is ripped apart as the citizens reveal their hidden sides and true natures, so Bill is forced to revise his list repeatedly, up until the last moment.

“One in a Thousand”, the second section, has Bill and his passengers discover that the lifeship isn’t quite as safe as they’d been led to assume. Turns out that the Earth governments, decided to give a maximum number of people a small chance to survive, rather than a small number of people a maximum chance to survive. Thus the lifeships have been built to absolute minimum standards. (Bill does some calculations and figures that to build the lifeships to the correct standards, the number of potential passengers would have to be one in one million Earthlings.)

The lifeship crew must find a way to survive the rigors of space travel and perhaps more importantly, the landing!

Finally, in “One Too Many” those of Bill’s complement that survived the journey (including Bill) must weather the many dangers of Mars if they hope to have a future at all…but the greatest danger may be one they brought with them!

The first part is the most suspenseful, since we know that Bill survives (he’s narrating the story from several years in the future) but everyone else is on the chopping block. On the other hand, it makes the narration feel oddly detached; Bill is doing his level best not to get emotionally involved, even though he’s making very emotional choices.

The second and third parts are more SFnal, though this was clearly written before any humans had gone into space, so the author has to guess what zero-gravity conditions are like, let alone the problems of surviving on Mars. It’s also notable that this potential future (deliberately, probably) has no technological advances beyond those needed to get to Mars–Bill has to make all calculations aboard ship with pencil and paper, apparently not even getting a slide rule to work with. Atomic power is mentioned as having stalled out.

And it’s very clearly a deliberate decision by the author not to have any social change whatsoever between the 1950s and “the future.” Simsville is very much an average American town of the Fifties, and the culture shock of what needs to be done to survive on the lifeship and on the new colony is from a very Fifties perspective. (The thought of miscegenation blows a lot of survivors’ minds.)

Some lapses are clearly down to 1950s standards and practices–there’s no mention of how waste elimination is handled aboard the lifeship. But others are just weird. The choices are kept secret until the absolute last minute so no one has time to pack, but none of the survivors had been carrying around a pocket Bible, or a pack of cards or even a family photo just in case?

And there are some skeevy bits. Okay, yes, the survivors on Mars are going to need to make lots of babies to ensure the human race has a future. But the standards listed for sexual assault are “if it’s a respectable woman who is trying to make babies with her respectable man, then the assault is to be punished severely, but if she’s a stuck-up rhymes with ‘witch’ that is denying society the use of her uterus, then the offender gets off with a wrist slap.” I can see, sadly, the male-dominated readership of the time going “Yeah, rough on the women, but got to be done.”

And then there’s the ending, where the bad guy essentially has Bill and his friends over a barrel and unable to act, so someone who’s gone “crazy” has to resolve the problem for them.

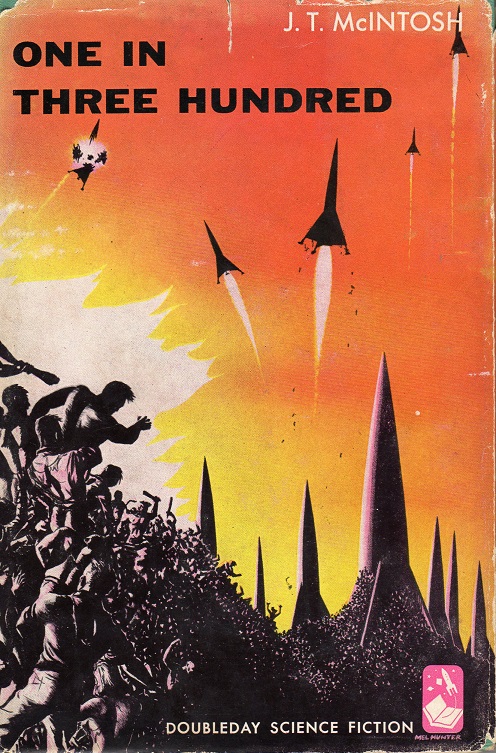

The cover is cool, but more symbolic than representative–in-story, the government has taken great pains to avoid such a scene. This was a Doubleday Selection of the Month, and the back cover copy is more about how science fiction is a popular and respectable literary genre now than it is about the book itself.

This is a good read, with the caveats mentioned above, but don’t think too hard because this is a “gee-whiz” story that will fall apart if you slow down to examine individual parts. Also, be aware that there are reprints that only have the first story, but don’t say so in the description.