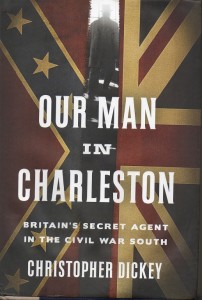

Book Review: Our Man in Charleston by Christopher Dickey

One of the great things about reading history books is learning about obscure people whose lives illuminate a corner of time. In school history classes, the emphasis tends to be on larger stories, a few “great men” (possibly a woman or two) and lots of dates to memorize. But a book that focuses on just one minor figure can tell you a lot about the time and place they lived in.

This volume concerns Robert Bunch, who was the British consul in Charleston, South Carolina from 1853-63. For our younger readers, a consul is a diplomatic official that handles the interests of a country and its citizens in an area of a foreign land less important than the capital, which is covered by an ambassador or minister plenipotentiary. The big issue when Mr. Bunch arrived in town was the Negro Seaman Act. In South Carolina and several other states of the southern United States, if a ship landing in a port had free black people in the crew, those crew members would be imprisoned for the duration of the ship’s stay. That meant those crew members couldn’t do the work necessary to get the ship ready to leave, as well as suffering the privations of prison. What was more, the ship’s captain was charged for the expense of imprisoning his crew, and if he couldn’t or wouldn’t pay, his ship and cargo would be seized by the government, and the crew members enslaved to pay the debt!

Since Great Britain had freed its slaves in the West Indies in the 1830s, and any British merchant captain operating in the West Indies hired locally, this meant that British citizens were being imprisoned, ran the risk of being enslaved and having their business prospects dampened. Her Majesty’s Government was not well pleased. On the other hand, the previous consul had been indiscreet about saying so, and was too forthcoming about the evils of slavery, so had been forced to leave town in theoretical disgrace. Mr. Bunch would have to be more discreet.

Meanwhile, South Carolina and its fellow Southern states were facing their own economic crisis. Their biggest crop was cotton, and their method of producing it demanded a steady supply of slaves. Back when the U.S. Constitution had been signed, it had been agreed to stop importing slaves from other countries (especially African ones) after 1808 as by that point, domestic production should be sufficient. They hadn’t realized just how heavily cotton would take off. Worse, the Northern “free” states were expanding their territory and economies faster than the slave states, and getting more disgruntled with slavery by the year. So the Southerners wanted to guarantee their right to have slaves forever, expand into places like Cuba and Mexico to increase their territorial power, and re institute the slave trade.

The British government was not thrilled with any of those plans, but they were well aware that their textile industry depended heavily on Southern U.S. cotton, which at the time had no viable substitute. So Mr. Bunch’s instructions were to be as subtle as possible about opposing such things.

What emerges is a remarkably sympathetic account of the two-faced behavior required of diplomats. In his interactions with the South Carolinians, Mr. Bunch was pleasant and friendly and non-committal, slowly working behind the scenes to accomplish British goals (it took several years, but the Negro Seaman Act was repealed.) But in his diplomatic correspondence and secret messages to his superiors, Bunch revealed his true horror about the practice of slavery and his belief that the people around him had gone insane in a fundamental way.

(Lest Northerners get too smug, most of the ships practicing illegal slave trading with Cuba and Central America at the time were built and funded by people in New York City, using their American flags to bluff their way past British anti-slavery patrols.)

When the American Civil War came, Mr. Bunch was the only competent British consul in the Confederacy. He was required to carry out secret diplomatic missions to try to get the Confederate government to pledge not to revive the slave trade–without ever making a solid promise to have Great Britain recognize the Confederacy as a separate nation. Meanwhile, his dispatches were part of the reason the United Kingdom held off on recognizing the CSA, despite the foreign policy blunders of U.S,. Secretary of State William Seward, who seemed ready to provoke war with Britain if that’s what it took to show the Union would not be intimidated.

Mr. Seward was also completely taken in by Mr. Bunch’s smiling facade, and decided he was in cahoots with the rebels, pulling his diplomatic credentials. When Mr. Bunch was evacuated from Charleston by a British ship in 1863, the South Carolina newspapers hailed him as a friend of the South.

The book comes with a center section of photographs, an extensive bibliography by subject (the book was vastly helped by Bunch’s diplomatic correspondence now being declassified), endnotes, acknowledgements and index.

Some thoughts: this book is very clear about the way the South Carolinians’ dependence on slavery and their doubling down on it being the only ethical mode of life led them in a death spiral that could only result in economic destruction, even if the Civil War had not come about. Make no mistake; at least for the elite of Charleston, the secession was all about keeping and expanding slavery (though their diplomats in European countries quickly resorted to all the other explanations you’ve heard, because slavery was a hard sell.)

Also, the peek behind the curtains of diplomacy makes me wonder what our own diplomats are up to around the world, and other countries’ diplomats are up to here. How much double-dealing is acceptable in a good cause? How can we ever be sure what an ambassador is really thinking? Was that really the best treaty we could get, or is something entirely different going on behind the scenes?

Highly recommended for American Civil War buffs, history fans and those who want to know more about how diplomacy works.

Disclaimer: I received this book from Blogging for Books for the purpose of writing a review. No other compensation was involved.

I have always felt that if history lessons were more about the story and less about the names and dates…it would be so much easier to learn and remember. I thoroughly enjoyed your review and your insights. Well done!

I think this book would make a good book club selection–it brings up interesting (if sometimes contentious) topics.

Fascinating review and topic!

Thanks!