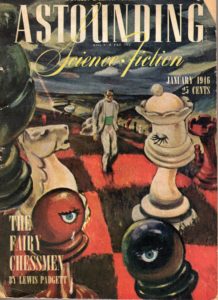

Magazine Review: Astounding Science-Fiction January 1946 edited by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Before Analog (see previous reviews), there was Astounding, the science fiction magazine that led the field for many years. Having gotten a copy of an issue from the pulp days, let’s take a look at what wonders lie within. Despite the cover date, the ads indicate it came out in early December 1945.

The lead and cover story is part one (of two) of “The Fairy Chessmen” by Lewis Padgett (a pseudonym for Henry Kuttner working with C.L. Moore.) It is roughly a century into the future, and the world is at war…again. After World War Two, the governments of Eurasia had crumbled, and reformed as the Falangists. They and America are the two superpowers and implacable enemies. Thanks to atom-bomb-proof shields and robot warfare, the war has stalemated for years.

Most Americans live deceptively peaceful lives in scattered communities on the surface, while the warmen toil in vast underground cities whose actual locations are closely guarded secrets. Low Chicago might be below the ruins of Old Chicago, or anywhere in the Midwest. Of course, in such conditions claustrophobia and other mental illnesses are a continuing concern, and it’s up to the Department of Psychometrics to keep the warmen in good mental health.

Which is why it’s concerning that Cameron, the head of the department, has been having hallucinations of eyeball doorknobs and talking clocks. He’s trying to keep it a secret, but his help is desperately needed by the War Department. It seems they have captured a scientific formula from the enemy, one that drives anyone who studies it mad (sometimes giving them strange powers in the process. For example, the levitating man who thinks he’s Muhammad’s corpse.)

There are time travel shenanigans involved, and one character seems determined to produce a specific future. The title comes from “fairy chess”, variants of the strategy game that use changed rules, such as a knight that can only capture backwards, or a 10×10 board. The formula changes the rules of physics, sometimes in mid-equation, and scientifically trained minds crack under the strain.

A nifty throwaway (probably) bit is the existence of “fairylands”, miniature cities with tiny robots that people play with ala the Sims. There’s also an amusing typo when one character claims he’s “half misogynist” when he means “misanthrope.”

Unfortunately, this novel is long out of print, so I have no idea how it ends. The cliffhanger is neat: “The edges of the spoon thickened, curled, spread into cold metallic lips. And kissed him.”

“N Day” by Philip Latham (pen name of R.S. Richardson) concerns an astronomer who discovers the sun is about to go nova. He tells the world, but is dismissed as a crackpot. (Had there been more time, someone would have checked his math and found him correct.) As a result, he finds his spine for the first time in decades.

“Veiled Island” by Emmett McDowell takes place on Venus (the pulp Venus of swamps and jungles.) A three-person anthropological team goes in search of the title island to investigate reports of a new variant of human. Apparently, unlike Earth, Venus just keeps producing new human variants out of the swamps which then climb up the ladder of civilization as they travel to the other side of the planet.

The Earthlings promptly crash-land, losing their clothing and supplies–they themselves have to start from scratch. While struggling to survive, they run into the new variant of humans they were looking for. A variant that seems destined to replace homo sapiens.

The sexism is pretty thick here, the action guy protagonist denigrates his female colleague for wanting to be treated as an equal, calling her a “tomboy” and the type who would have been a suffragette back in the day. (Apparently something like feminism happened in this future, but he’s not too keen on the results.) Over the course of the story, she comes to realize how awesome he is, and they are planning to get married (in the now considered barbaric Twentieth Century fashion) at the end.

The evolutionary science is suspect–emotionlessness is viewed as a huge evolutionary advantage that will allow the new species to outcompete other humans and replace them.

“A Matter of Length” by Ross Rocklynn (pen name of Ross Louis Rocklin) takes place in a far future with galactic travel. A stable mutation has created a new kind of human, the “double-brained” Hypnos, who have the ability to hypnotize ordinary humans. They are not physically distinguishable from other humans, but can be detected by “Sensitives.” Hypnos face severe prejudice, and there’s a war going on between societies that want to exterminate them and those that tolerate them.

All that is background. A Hypno named Joe has been captured by anti-Hypno forces, and was being shipped back to their planet for a show trial and execution when the ship went off-course and landed on a planet where time has gone wonky. There’s a paranoid belief among some of the crew that Joe somehow caused this, or is making them hallucinate this, despite the anti-mind control forcefield surrounding his cell. Eventually, the time wonkiness allows Joe to escape, and he rescues the two people on the ship who are not entirely anti-Hypno.

It turns out that Hypno powers have been vastly exaggerated as propaganda by the anti-Hypno forces; Joe never actually uses his mind control abilities during the course of the story. It’s the holding cell force field that gives him the temporary advantage he needs as it shields him from the time wonkiness for a while. Keitha, the Sensitive woman who tracked him down, is dismayed to learn that she’s next on the extermination list after all the Hypnos have been eliminated (as Sensitives are Hypno/ordinary human crossbreeds.)

Apparently, there are also longevity treatments in this future, as the captain of the anti-Hypno ship holds a grudge against the Hypnos for the death of his daughter nearly a century before, with the war starting later. (It’s a “failure to save” instance–a doctor who was secretly a Hypno couldn’t cure the daughter from a fatal disease, and when his secret was revealed, he was lynched for deliberately killing a human girl.)

“The Plants” by Murray Leinster takes place on a planet with only one form of life. Plants with flowers that follow the sun…or anything unusual that happens. Four men whose spaceship was sabotaged crash-land on the planet. Are they more in danger from the pirates that sabotaged the ship for its precious cargo…or from the plants? A story that has some creepy moments, and could have gone full on horror if the author wanted.

“Fine Feathers” by George O. Smith is the final fiction piece. It’s a science fiction retelling of the fable “The Bird with Borrowed Feathers” usually ascribed to Aesop. A ruthless businessman discovers a way to artificially boost his intelligence by energizing his brain. The process renders the user sterile (somehow) but since he wasn’t interested in having children, Wanniston considers that a small price.

Being superhumanly intelligent gives Wanniston a huge advantage over his fellow Earthmen, and he is soon the most powerful businessman on the planet. But he yearns for more, and when a suicide trap makes it untenable for Wanniston to stay on Earth, he decides to join Galactic civilization, where dwell people who have come to super-intelligence by eons of evolutionary processes. He keeps using the brain energizer, and is soon even more intelligent than the Galactic Ones.

Being logical beings, the Galactic Ones recognize Wan Nes Stan’s (as he now calls himself) superior intellect, and are willing to install him as their leader…as soon as his experience catches up to his intelligence in a few centuries. Wan Nes Stan tries to shortcut the process, only to discover his true limitations and destroy himself.

The story bookends with identical dialogue at the beginning and end, which would be effective if the language in those conversations wasn’t so stilted. It also uses the 10% of your brain gimmick (which admittedly was less debunked back then.)

John W. Campbell’s editorial “–but are we?” is prescient on the subject of nuclear proliferation though thankfully humanity has survived so far.

There are two science fact articles. “Hearing Aid” by George O. Smith is a very short piece on radio proximity fuses. “Electrical Yardsticks” by Earl Welch is about the international standards for the volt, ampere and ohm; how they were decided, and how they are maintained. Lots of math here, and possibly the technology is dated, but likely fascinating reading if you want to know more about electrical engineering.

I liked the Leinster piece best because of the thin line it walks between horror and SF; “The Fairy Chessmen” has some great imagery, but with only part one I can’t judge its full effectiveness.

Overall, an average issue, but well worth looking up for old-time science fiction fans.